William Henry Jackson: Pioneer Photographer of the American West

![]()

The story of the American West is filled with many characters and large personalities. How the West was won or lost, depending on which side you were on, can be told through the lives of many people. Not all were cowboys, outlaws, gamblers, or lawmen like are often portrayed in the movies and novels; some were photographers. One of the photographers whose story looms large is William Henry Jackson.

Jackson was also a painter and often combined the two skills by hand-tinting photographs, both his own and for other photographers. As a teen, he did hand-tinting and retouching for photography studios around Vermont.

The Civil War

Jackson served in the Civil War as part of the 12th Vermont Infantry where he saw action at the Battle of Gettysburg. After the war, he moved to Omaha, Nebraska, which was on the edge of the frontier at the time. There he opened a portrait studio with his brother, but by his own admission, traveling and landscape photography were more appealing to him than the portrait business.

Omaha was the headquarters of the Union Pacific Railroad, which commissioned him to photograph scenic views along the route for publicity and advertising for the railroad. This began a long relationship with the railroads as a photographer and illustrator.

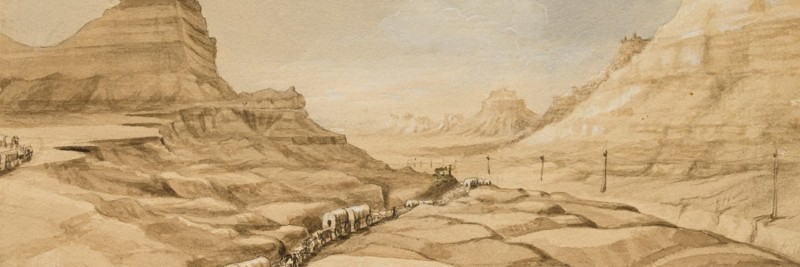

From Omaha, he made many “photographic campaigns” west to photograph and paint landscapes as well as the people of the region. In 1869, the publisher E & HT Anthony, which later became Ansco, commissioned him to provide 10,000 stereoviews of western landscapes. He was also hired as the official photographer by the U.S. Government for the Hayden United States Geological Survey.

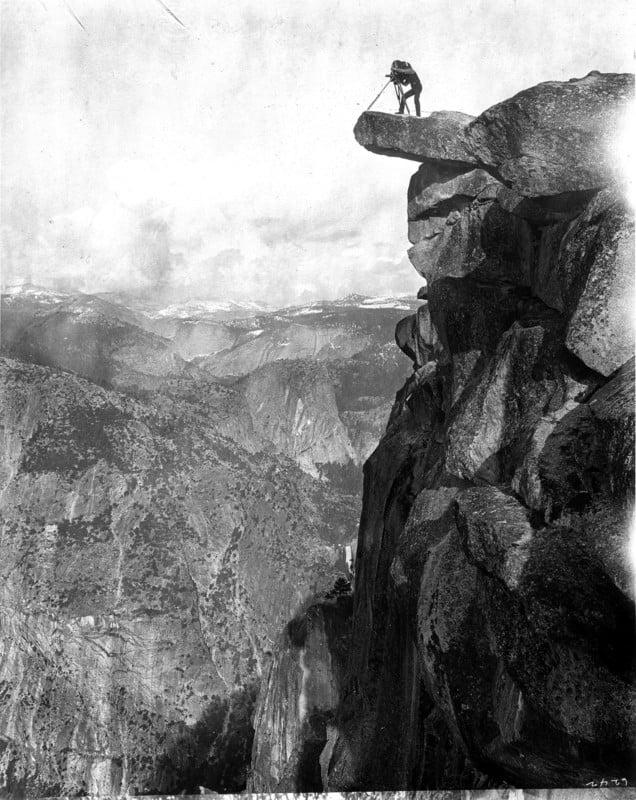

He spent summers for eight years as part of the Hayden team, making thousands of large format images primarily with a 20×24 camera. This was the wet plate era which meant he had to haul hundreds of large glass plates in a horse-drawn wagon, set up the very large camera, coat the plates in a dark tent, expose the image in the camera and develop the plates before the emulsion dried. He did this thousands of times in some of the most difficult conditions imaginable.

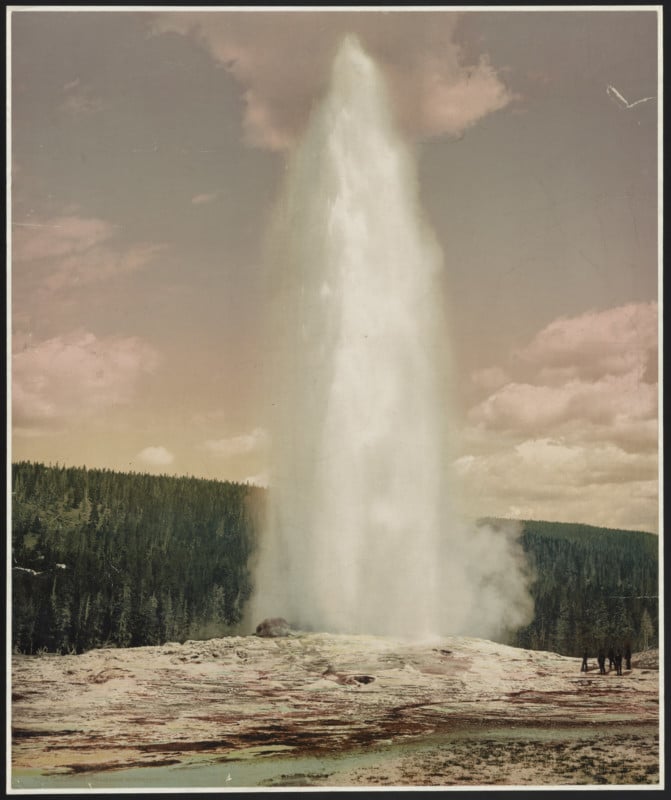

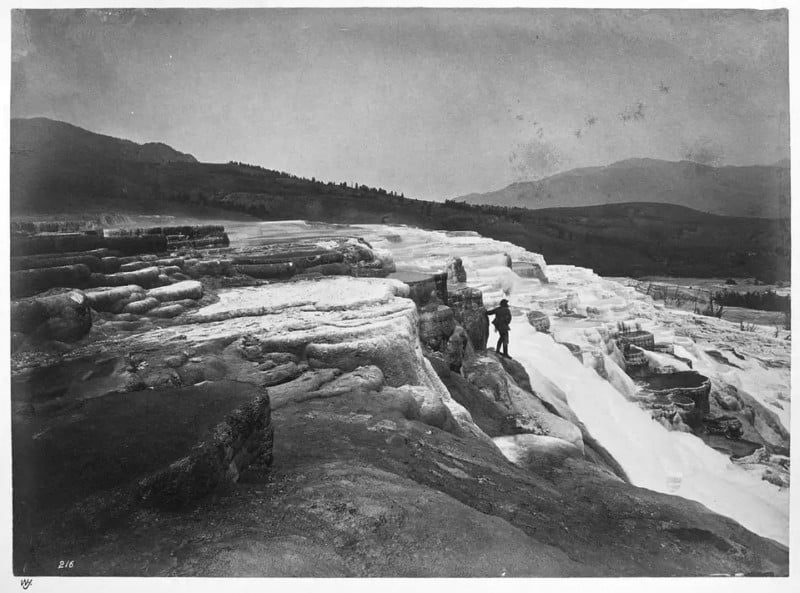

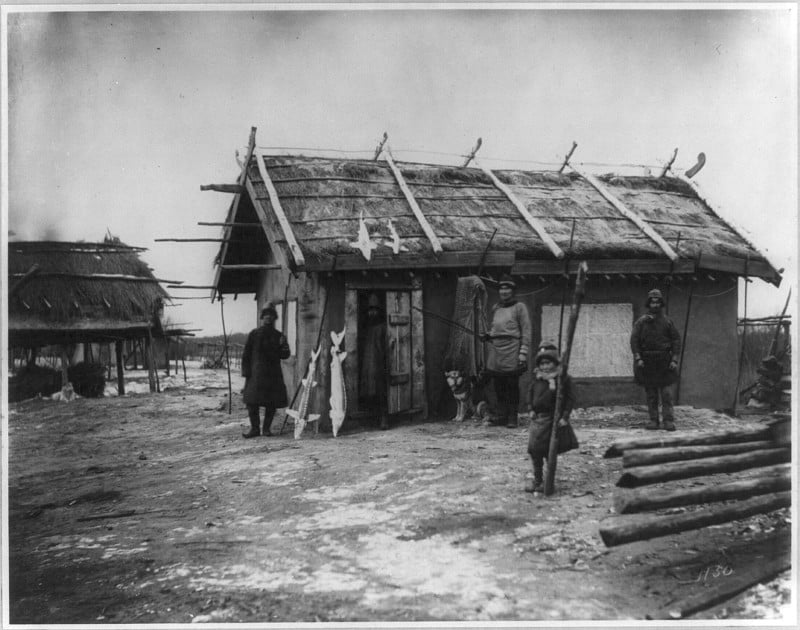

Jackson thus became the first person to photograph Yellowstone, Mesa Verde, Mammoth Hot Springs, the Colorado Rockies, and much more. He was friends and worked closely with the painter Thomas Moran on the surveying projects. Jackson was also said to be the first person to photograph the Pawnee, Otoe, Omaha, Winnebago, Ponca, and Osage Indian tribes.

Yellowstone

The Yellowstone Region of Wyoming had been a source of fantastic stories of boiling lakes, soaring waterfalls, and hot water shooting hundreds of feet in the air. Most were considered far-fetched or myths at best. When Jackson showed his beautiful photographs of Yellowstone to the US Congress, they were compelled to designate Yellowstone as the first National Park on March 1, 1872. Since there was no National Park Service, congress sent the Army to set up a post and patrol the area. Fort Yellowstone at Mammoth Hot Springs was active until 1917 when the National Park Service took over the care and management of the National Parks.

A Successful Businessman

In 1873 he sold 40,000 negatives to the Edison Institute in Detroit and the Denver Public Library bought 2,000 photographs of the Rocky Mountains for their permanent collection.

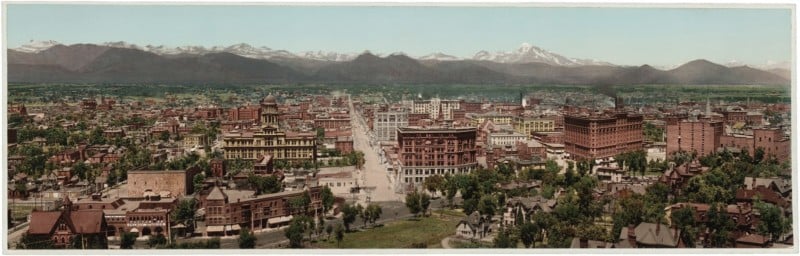

In 1879 Jackson moved to Denver where he started a large successful photography business called, “The Jackson Photographic Company.” There he had a large staff including a printer, mounter, retoucher, and two receptionists. Over the next fifteen years, he made over 30,000 negatives for the railroads. He also published books, posters, and various other photographic-related items such as postcards and stereoviews.

He traveled internationally as well. From 1894-to 1896 he was with the World’s Transportation Commission where he became known as the “Great American Ambassador,” making many photographs in the Near and Far East, Australia, China, and Siberia/Russia.

![]()

In 1897 Jackson accepted an offer from the Detroit Publishing Company, which was a major manufacturer of postcards and stereoviews, becoming a major shareholder and manager. The Detroit Publishing Company drew from its collection of 40,000 negatives to sell about 7 million images annually. For most of that time, Jackson was the production manager which left him with little time to travel. He held that position until 1924 when he was 81 years old.

The Detroit photographs are now split between the Library of Congress and the Colorado Historical Society. Most of these photographs are currently available online at the Library of Congress.

The Department of the Interior hired him in 1935 to paint four large murals depicting scenes from the Hayden Surveys of the 1870s to 1880s for the new Department of Interior Building.

Later Life

Throughout his long career of almost 90 years, Jackson photographed and painted many subjects and scenes that are now embedded in our view and understanding of the American West.

His autobiography, Time Exposure, is still available.

![]()

One of his last jobs was acting as a technical consultant for the movie “Gone with the Wind.” With a long list of experiences going back to the Civil War and before and his massive collection of images, photographs, and paintings, there was likely no one better qualified for that task.

In 1941, Jackson was interviewed about his experience of roaming the Wild West as a photographer.

Jackson died in 1942 at the age of 99 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He is now in the International Photography Hall of Fame which provided some of the information for this article. There is much more information available from a variety of sources, including his autobiography, for those interested in a truly significant photographer and businessman and an accurate story of the old west.

Those of us who have followed in William Henry Jackson’s and the other pioneer photographers’ paths continue to be amazed at the tenacity and pure effort that these early photographers exhibited to get these great photographs. Now we can travel to these same locations on paved roads in modern vehicles and use modern high-performance digital cameras that give better images than even the 20×24 glass plates that Jackson sometimes used.

We need not feel guilty at how easy we have it today, but rather be grateful and thankful for those pioneer photographers that went before us.

For more information and references, here are some of the resources used in this article:

- The International Photography Hall of Fame in St Louis, Missouri

- Time Exposure, the autobiography of William Henry Jackson

- Photography: The Early Years by George Gilbert (1980)

- The History of Photography by Beaumont Newhall (1964)

- Second View, The Rephotographic Survey Project, a project to rephotograph the scenes from the early western photographers published by the University of New Mexico Press. (1984)

There is also an extensive article about William Henry Jackson on Wikipedia.