Philippe Halsman: American Portrait Photographer to the Stars

Philippe Halsman was born in Riga, Latvia, on May 2, 1906. He discovered an old view camera in the family attic when he was fifteen, bought some glass plates, and started making photographs. Like many other photographers, when he first saw that image appearing in the darkroom tray, it was a life-changing moment, and he knew what he was going to be doing with his life.

His sister moved to Paris to study and married a Frenchman. Attending their wedding, he fell in love with Paris and decided to move there to continue working on his engineering degree. He was far more interested in art and literature than he was in technology and mechanics, so after he graduated, he announced that he was a professional photographer. He bought a photoflood lamp and a used enlarger to go with his old view camera and launched his career.

He soon became well-known in Paris for his creative and strong portraits of actors, writers, and musicians. He married his apprentice, Yvonne Moser. Soon Philippe and Yvonne Halsman became a famous photography team in pre-war Paris. He bought another floodlamp, a light stand, and a Zeiss Tessar lens. The ultra-sharp images and creative two-light setups became his signature.

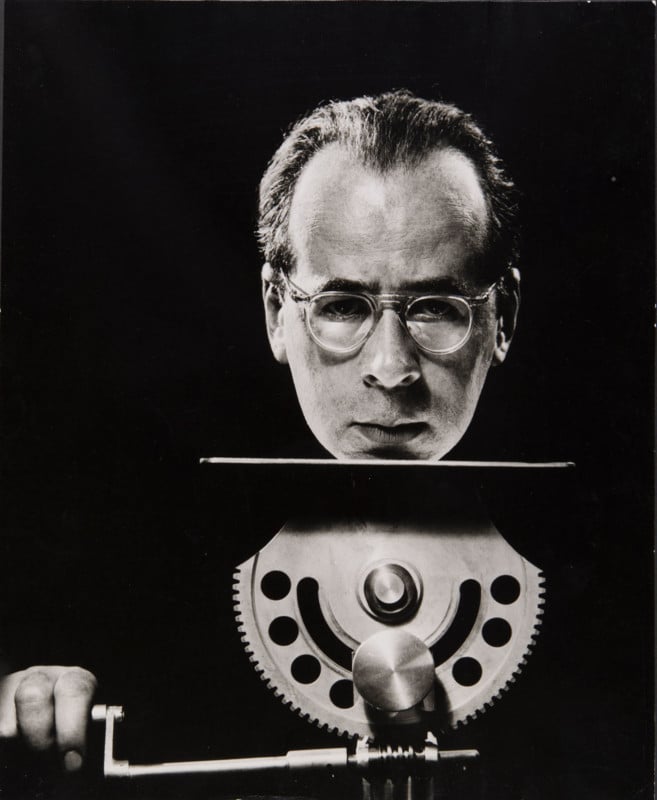

Halsman Camera

Halsman soon realized that in the seconds that he lost loading the film holder and pulling the dark slide, he had missed the decisive moment of a photograph. This caused him to design a 9×12 cm twin-lens reflex. There were a number of TLR cameras that he designed and had built or sold as “The Halsman” camera, most notably 4×5 TLRs.

“The camera I have constructed for myself is a very important part of my technique,” Halsman once said. “My head is covered by the focusing cloth, I am looking at the subject through the lens. From the sitter’s point of view, the camera’s lifeless mechanism suddenly becomes almost alive.

“Later, in the darkroom I sometimes get a new idea. The creative process doesn’t stop with the taking of the picture, it continues also with the making of the print — because by changing the tonal values you can change the mood or emphasize the statement you originally intended in the studio.”

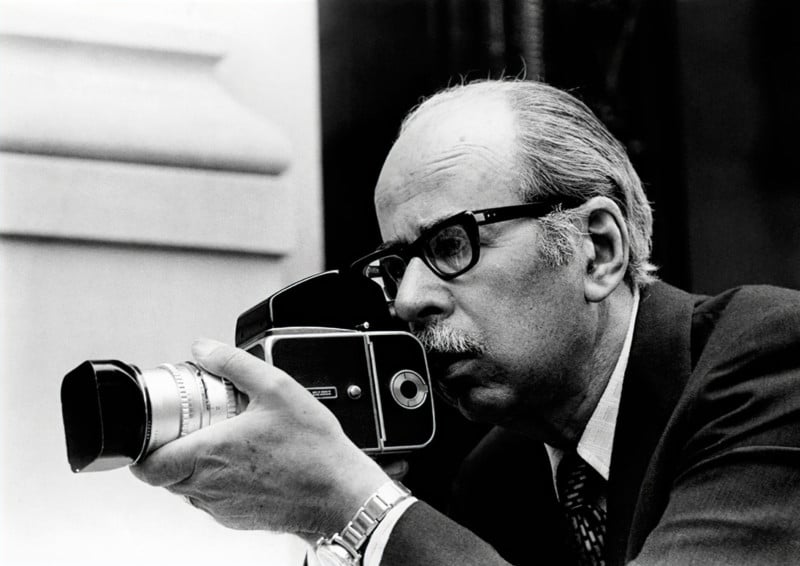

He also used Hasselblads, Rolleiflexs, and other twin lens reflex and single-lens reflex cameras. He wanted to be able to be continually seeing the subject through the viewfinder as he fired the shutter.

World War II

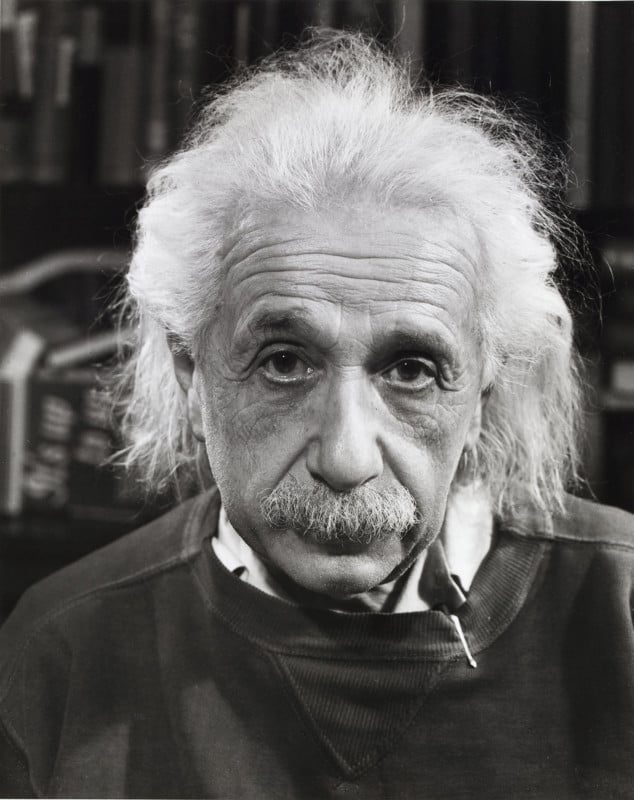

When the war started, he was able to send his wife and first-born daughter Irene to the United States. When the Germans overran Paris, he fled south with many other Parisians to Marseille. There, he found that he would not be permitted to go to the U.S. because he had a Latvian passport. The U.S. allowed only eighteen Latvians per year to enter the country and there was a seven-year wait. Because he was acquainted with Albert Einstein, he asked his wife to contact Einstein to see if he could help. Einstein did indeed help and Halsman was soon on his way to New York.

Halsman arrived in New York on November 10, 1940. Even though he was a famous photographer in France, he was unknown in New York. He spoke five languages, but English was not one of them, so he was at a big disadvantage. His breakthrough came when his photograph of an aspiring model named Connie Ford was picked up by the beauty company Elizabeth Arden and used for a lipstick ad. The photo won The Art Directors Medal, and his career took off in America.

Salvador Dali

Halsman met Salvador Dali in the early 1940s and they became lifelong friends. Over the years Halsman photographed Dali many times.

One of the most famous images Halsman made of Dali was Dali Atomicus in 1948 — the photograph with the cats, water, and a chair.

Hearing Halsman describe this photo shoot in person was hilarious. In the mid-1970s, the local college in my town held a series of lectures called “The Masters of Photography.” They invited several famous photographers of the day to speak at the monthly public event. I attended all of the events and was able to meet many of the most famous 20th-century photographers. The evening with Philippe Halsman was one of my favorites.

He described throwing the water in the air while his wife held the chair his sister Liouba and daughters were the “cat wranglers.” It took 26 shots to get this image. That meant 26 times wiping up the floor, 26 throws, and 26 times catching the cats.

Jump Book

Early in his career, he got in the habit of asking his portrait subjects to jump. This was usually the last photo of the session. Over the years he made hundreds of images of famous people jumping that he published in a series of books called The Jump Book.

“Starting in the early 1950s I asked every famous or important person I photographed to jump for me,” Halsman once said. “I was motivated by a genuine curiosity. After all, life has taught us to control and disguise our facial expressions, but it has not taught us to control our jumps.

“I wanted to see famous people reveal in a jump their ambition or their lack of it, their self-importance or their insecurity, and many other traits.”

Using jumping as a pose to gain insight into his subjects’ psyche was a psychological tool the Halsman termed Jumpology.

Life Magazine

A fashion story about ladies’ hats led to a Life magazine cover. He soon was shooting portraits for Life magazine. In the post-war era, having a photograph on the cover of Life magazine was the highest achievement a photographer could have. Halsman eventually had 101 Life covers, more than any other photographer. The 100th cover was of Johnny Carson in 1970, and Life published an inset featuring a self-portrait of Philippe and Yvonne with the title “The King of Covers Shoots his 100th.” That portrait of the duo was actually the photograph that the Halsmans made for their 1969 Christmas card.

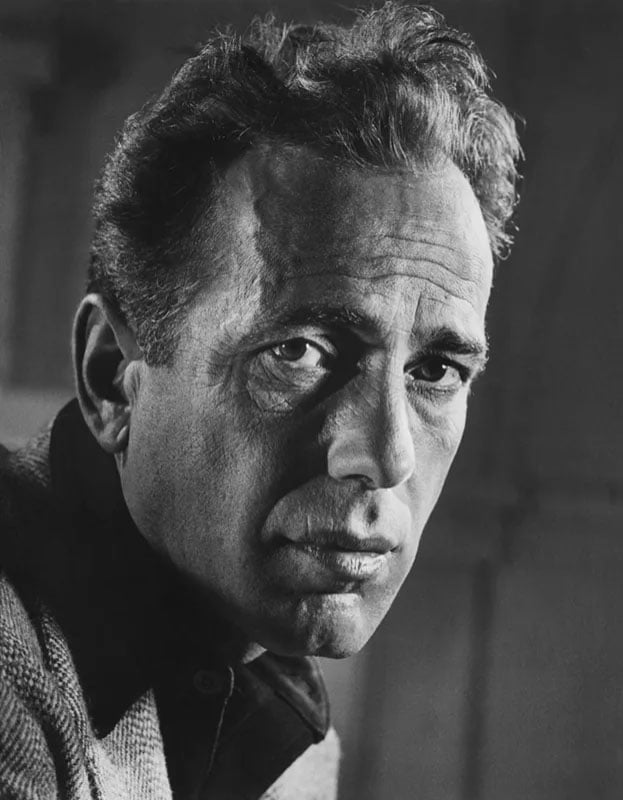

In Halsman’s description of his work, he said, “It is important to remember that a portrait sitting is an extremely artificial situation. Very few people are able to lose their self-consciousness immediately and behave in front of the camera as though it were not there. In almost all cases the photographer has to help the subject reveal himself. In many sittings I have felt that what I said to the subject was more important than what I did with my camera and my lights.

“My great interest in life has been people. A human being changes continuously throughout life. His thoughts and moods change, his expressions and even his features change. And here we come to the crucial problem of portraiture. If the likeness of a human being consists of an infinite number of different images, which one of these images should we try to capture? For me, the answer has always been, the image which reveals most completely both the exterior and the interior of the subject.”

“Such a picture is called a portrait. A true portrait should, today and a hundred years from today, be the testimony of how this person looked and what kind of human being he was.”

Philippe Halsman died in New York City on June 25, 1979, at the age of 73 after a brief illness.

Much of the information for this article was from the book, Halsman Portraits by Yvonne Halsman.

Image credits: All photos by Philippe Halsman © Halsman Archive