The Rise and Fall of the Press Camera

![]()

If you were an aspiring photojournalist during most of the 19th and early 20th centuries, then your dream machine was likely not a Hasselblad, a Rolleiflex, a Leica, or any of the other vintage film cameras commonly cited as the most desirable collectibles nowadays.

These were incredibly tough, purpose-built machines tailor-made for the needs of reporters – including those working in dangerous environments, such as war photographers. For a significant period of photography history, press cameras remained among the most fully-featured and expensive gear that any shutterbug could dream of.

Let’s back up a bit. What actually is a press camera, black-on-white? And what made these engineering wonders disappear from the face of modern photography?

That is going to be our subject for today. In this article, we’ll take a deep dive into the fascinating story of the press camera, from its birth and fame all the way to its fall into relative obscurity.

The Origins and Rise of the Press Camera

Even during the infancy of photography as a medium, some manufacturers already thought of the potential in marketing a camera that is compact enough to be hand-held.

Cameras of the late 19th century were usually made of wood with brass shutters and lenses. These materials can be tough and resilient yet remarkably lightweight, especially compared to steel. This actually made “compact” cameras quite feasible to build and cheap to sell, and many examples of such designs survive to this day.

In a sense, it’s not the cameras themselves that failed to entice journalists to use them, but rather their medium.

Collodion wet plates, the most popular imaging medium of the late 1800s, had to be developed right after exposure, meaning photographers needed their own portable darkroom equipment to take with them into the field. Furthermore, film speed (or rather plate speed) was very limited – only a few ISO at most, and fractions of a single ISO in the case of low-performance plates!

This, combined with rather slow lenses, meant that long exposures were necessary at any time of day, no matter the subject. And thus, walkabout photography, including live coverage and reportage, remained a pipe dream.

Then, in the 1890s, the whole paradigm got turned on its head. Dry plates, which could be developed at any time after exposure, advanced rapidly in performance thanks to advances in chemistry.

This, along with other advancements in photographic technology that occurred in parallel around this time, opened the floodgates for a whole new breed of cameras.

The First Generation of Press Camera, ca. 1900-1920

One early example is the Goerz-Anschütz – an entirely unknown name today, but one that carried serious cachet back then.

This was a box-type camera made out of wood. Both the viewing screen and the entire lens board extended and retracted along struts and leather bellows to make the camera compact enough to fit easily into a bag.

The real appeal behind the Goerz-Anschütz wasn’t just its size, but rather its shutter. Developed using an extremely innovative focal-plane design, the so-called rouleau shutter of the Goerz-Anschütz was capable of a top speed of 1/1000th of a second – as early as 1894!

On the top of the body was the Ango’s other killer feature: its viewfinder. Before the Goerz-Anschütz and others like it, the vast majority of cameras used a glass screen for focusing.

This was precise and easy to use, but it was slow, as anyone experienced with modern large-format view cameras can attest to!

Enter simple external viewfinders. The Ango, in its case, used a Newton-type finder, which is basically a metal frame with a simple glass front lens and a gunsight-like reticule close to the user’s eye for precise composition.

These kinds of viewfinders, of course, couldn’t correct for parallax, preview focus or depth of field, or do any of a number of things that we nowadays expect when we look into the eyepiece of a camera.

That’s why the Ango, and countless similar designs after it, would retain the glass viewing screen in the back in addition to the “live-action” viewfinder on the top of the body.

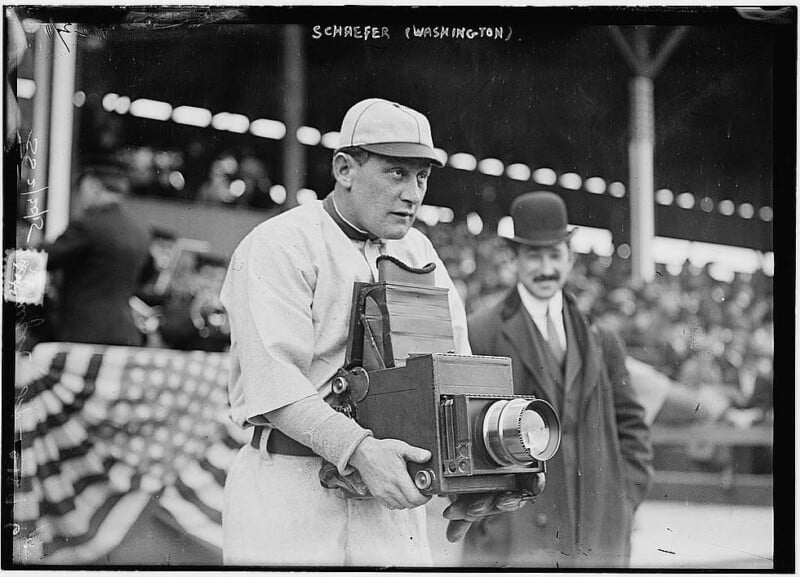

All of its innovative features made the little Ango a runaway hit all over Europe and North America. Reporters were the ones popularizing its use the most, showcasing its capabilities for documenting fast action with that trick shutter.

Though it wasn’t officially referred to as such, that might make the Goerz-Anschütz camera one of the first press cameras ever made.

Worldwide Success Thanks to the Press SLR, ca. 1925-1940

For a few years, the top dogs in the emerging press camera field were strut folders like the Ango. However, it wasn’t long before a competing design would emerge. That design was the large-format, single-lens reflex press camera.

Yes, you read that right: SLRs in the year 1920!

Aiming to combine the bright viewing and accurate focusing of a glass screen with the speed and versatility of an external viewfinder, camera engineers came up with a flipping mirror design.

This mirror could alternate between exposing plates (or film, which was rapidly gaining in popularity) and displaying a reflected image of what the lens saw. In other words, it’s very much the principle still used in DSLRs of today, a whole century later – with one major caveat: prewar SLRs had no pentaprism.

The unique properties of such glass prisms, let alone how to manufacture them with precision, were still a mystery. This meant that SLR press cameras reflected the image produced by the lens not in line with the horizon, but rather upwards, and flipped left-to-right.

Hence, the user experience of such SLRs is a lot more akin to a waist-level viewfinder twin-lens reflex from the 1950s, and remains so until firing the shutter, when a dramatic and extremely powerful mirror slap kicks in.

Despite the added weight and heft of the swinging mirror, the intimidating sound profile of the shutter, and the very high price of these machines, they established themselves as the ultimate must-have among professional journalists.

Because this was the time period when photography seriously established itself as an essential aspect of news reporting, and because contemporary SLRs looked so distinctive with their raised viewing hoods and attention-grabbing shutter sounds, it was during the 1920s that the term “press camera” was coined.

For the most part, that referred to the highly-priced elite of SLRs: brands like Pressman (get it?), Graflex, and others were the cream of the crop.

But Angos, as well as other brands of strut folders like the VN Press and the Roth, continued to be hugely popular for their small footprint and began to be called “press cameras” around this time as well.

The Glitzy Glamour of the Press Camera During the Art Deco Period

It is towards the tail end of the 1930s that press cameras continued to rapidly evolve until reaching their most iconic and recognizable form yet. I am talking, of course, about the Graflex Speed Graphic.

Graflex had already been a maker of very competitive large-format press SLRs as early as 1898, so they had more experience than most. They could also rely on the feedback of countless working photojournalists as a reference for improving on their designs.

The successor to their popular SLRs was unveiled in 1912 and didn’t immediately catch on. It had some great features, such as interchangeable lenses and a relatively lightweight body that was easy to hold. Alas, its high price and the dominance of SLRs confined it to the sidelines.

It wasn’t until the peak of the Jazz Age, in 1928, that Graflex would release a revised version. This Speed Graphic, armed with a much wider, faster lens selection, many ergonomic improvements, better viewfinders, and tons of other goodies, became a runaway hit.

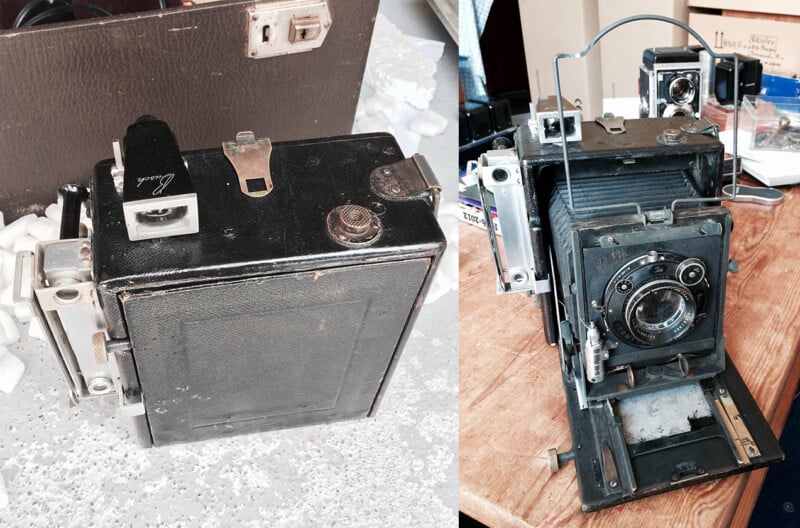

Instead of reinventing the wheel, the Speed Graphic was all about versatility. It combined features seen on other types of cameras into one universal body that could do just about everything.

With its ground glass screen and fast telephoto lenses, it was a capable studio portrait machine.

But thanks to its precise rangefinder in addition to auxiliary viewfinders for tracking moving subjects, the Speed Graphic excelled outdoors in the field, too.

Its focal-plane shutter went up to 1/1000th of a second – but many of its standard lenses came with their own built-in leaf shutters, which the photographer could employ alternatively to reduce noise.

That huge combination of excellent features and the existing reputation of Graflex meant that the Speed Graphic became the press camera of the middle of the century. Competitors, like the Busch Pressman and the Linhof Technika, were equally beloved and appreciated by their users, but none matched the Speed Graphic in terms of reputation or pop culture recognition.

Put on a Hollywood movie from the ‘Golden Age’ of the 1930s or 40s, or even a modern production set in those times, and you’re likely to spot at least a few chromed-out Speed Graphics wherever journalists come into the scene.

In fact, the dominance of the Speed Graphic was so great that every single Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph until the year 1953 was taken solely with this specific make and model of camera!

![]()

The Press Camera in Crisis

What happened after 1953?

For that, we need to take a look at the crisis period of the press camera. This crisis began, ironically enough, right at the peak of its popularity, in the year 1925.

Prologue to Crisis: The Leica Enters the Fold

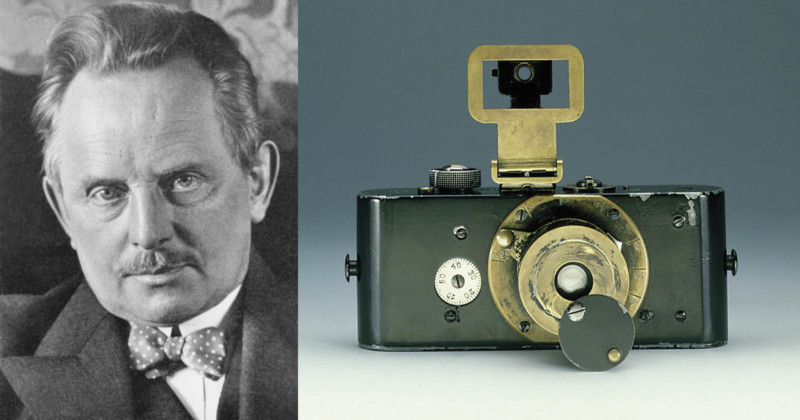

That year, a genius inventor from Germany named Oskar Barnack displayed to the public his design for an ultra-compact, “miniature-format” camera using 35mm motion picture film.

The Leica, as it was called, was not an overnight success outside of its home country, much like the Speed Graphic. But refinements and improvements made it an extremely compelling design, adding an interchangeable lens mount, a built-in rangefinder for focusing, and more.

By the late 30s, Leicas were among the most widely-sold cameras ever made up to that point, vastly outselling Graflexes and only topped by cheap, mass-market box cameras like the Kodak Brownie.

Despite the Leica’s obvious advantages in speed and size, members of the press mostly rejected it as a camera for amateurs. That was chiefly due to one issue: the dimensions of those tiny 35mm negatives. In the 30s, enlarging photographs was still mostly considered an esoteric practice, and newspapers and magazines alike wanted big prints for their front pages and spreads.

For some time, these voices kept the success of the Leica relatively at bay. While artists and Bohemians flocked to the camera and it even found a healthy niche in scientific, street, and fashion photography right away, journalists would not yet adopt it en masse.

World War Two and Its Effects on Photojournalism

In the bloody, disorienting, and fast-paced battlefields of Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific, the weaknesses of the Graflex-style press camera started showing.

Yes, the Speed Graphic was incredibly versatile, but it achieved this versatility by means of redundancy. Its focal-plane shutter was complex, heavy, loud, and hard to service impromptu in the field. Depending on the version, it featured up to three different kinds of viewfinders plus a separate rangefinder, adding bulk and complexity.

Everything from changing lenses to reloading (which was necessary after every single frame) was time-consuming, complicated, and prone to error.

That is why many journalists, especially those on the frontlines, switched to lighter, leaner alternatives. The US-made Argus C3, a boxy, palm-sized 35mm rangefinder camera, was made in the millions and became an excellent pocketable “sidearm” for thousands of PJs.

Military attachés and those working in intelligence or in the Signal Corps would make use of the Kodak Medalist, a medium format rangefinder shooting 6x9cm exposures that was specifically developed for wartime.

For every way in which those smaller cameras were more capable, there was one huge weakness letting them down – the limitations of printing small negatives.

While not every negative would need a large print, especially in a military economy, higher-ups in the defense industry as well as journalists themselves increasingly became interested in the idea of developing more advanced enlargement techniques to get higher-quality, larger-scale prints out of smaller pictures and compact cameras.

The Japanese Invasion

Despite technological advances and changes in mood, the American-made, large-format press camera actually remained alive and well throughout the postwar 1940s.

In fact, the Graflex Speed Graphics made during this period were the brand’s best-selling models yet!

However, the writing was on the wall. The final nail in the coffin for the old-style press camera would soon follow with the two defining wars of the 1950s, the Suez War and the Korean War.

In these engagements, once more the value of pocketable, ultra-compact cameras that could shoot large series of images became apparent to photojournalists.

One of them, a certain David Douglas Duncan, experimented with lenses by an odd Japanese maker called Nippon Kogaku, recommended to him by a friend from the then-American-occupied country.

These lenses strapped to a Leica camera revealed unbelievable levels of sharpness and detail retrieved from the tiny 35mm negative. That was something that many in the industry had refused to believe was possible, and something that Duncan exploited by making large, provocative prints of his work to be displayed in major magazines.

Nippon Kogaku’s lenses, with someone of Duncan’s caliber as their spokesman, caught on like wildfire. It was also around this time that the company designed its own camera, a Leica-inspired rangefinder with touches of Contax that was called the Nikon I.

Eventually, the Nikon would morph from a rangefinder into a compact SLR with a pentaprism in 1959. That camera was the groundbreaking Nikon F. The entire company would rename itself in honor of this record-breaking camera soon after.

With its reputation for war-proven reliability, easy ergonomics, 36-shot rolls of 35mm film that provided excellent results for most press work, and Duncan-approved lenses, the Nikon F SLR ticked all the boxes for journalists of the 60s. It looked like the camera of the future.

There’s just one problem with that: the Nikon didn’t just sell well with journalists.

How the Press Camera Vanished

Becoming one of the top-selling camera designs of all time and inspiring myriads of competitors, Nikon’s SLR camera series ruled the photographic landscape for nearly the entire second half of the 20th century.

From war photographers engaged in Vietnam and Burkina Faso to local news reporters in France, and from casual street shooters to landscape photographers and others – just about everyone either had or wanted to have a Nikon, a Pentax, or a Minolta, to name only a few of the available options.

There were attempts to revive the idea of a dedicated, distinct “press camera” during the early years of SLR adoption. For example, Mamiya presented an oddly retrofuturist machine called the Mamiya Press in 1960. This camera was highly modular and could shoot 6×4.5, 6×6, 6×7, and 6×9 medium-format exposures on either roll film, sheet film, or plates.

It came with a variety of well-reputed Mamiya lenses, a hand grip that doubled as a remote shutter release trigger, and a built-in rangefinder as well as provision for a ground glass screen and leather bellows.

In other words, it took all the features that the Nikon lacked over the Graflex Speed Graphic, left out or streamlined the rest, and downsized the whole thing to make it a lot lighter and more capable.

While this was appreciated by some, especially journalists working for large-print magazines as opposed to newspapers, the Mamiya Press did not serve the role it was originally meant to.

Never truly replacing 35mm Nikon-style SLRs as the tool of choice among photojournalists, it instead was more and more heavily marketed towards studio photographers as time went by.

The same is true for all of Mamiya’s later models, which were similarly developed with press journalists in mind but never found a solid footing in that market.

Graflex itself would stop production of the Speed Graphic in the year 1973. By that point, sales had already slowed down to a crawl, and the press camera market was declared effectively dead.

What the Press Camera Left Behind

You probably know the rest of the story already. SLRs would continue to be the end-all and be-all of 20th-century photojournalism until the very end, only to be replaced by digital SLRs during the new millennium, and eventually, mirrorless cameras more recently.

In that sense, the answer to the question “What happened to the press camera?” is clear.

The press camera as such never died. Instead, outgrowths and developments of earlier press camera designs, culminating in the Nikon F SLR, were so versatile and effective that they ended up conquering areas far beyond that of journalism which they were originally designed for.

As for the other question we mentioned in the beginning, what the press camera was in the first place, that is actually somewhat harder to answer. If you asked a reporter a hundred years ago, he would probably point you to either a strut folder like the Goerz-Anschütz or an SLR like the original Graflex.

Only a few decades later, rangefinders like the Speed Graphic would become the quintessential press camera, embedded into the public consciousness as the journalist’s everyday tool.

Even later, the pentaprism SLR would take its place. While the term “press camera” eventually vanished, you could easily argue that the Nikons and Pentaxes of that era, as well as the top-of-the-line DSLRs and mirrorless cameras of today, are press cameras, too.

After all, one thing has not changed so much over the last 100 years: the needs and demands of professional journalists continue to dictate the research, development, and marketing of the most capable and expensive cameras in the world.