Minolta: Tales of a Forgotten Camera Maker

![]()

Today, most of the consumer-grade camera landscape is dominated by less than half a dozen brands. Canon, Sony, and Nikon take the lion’s share in terms of sales and public recognition, while almost all the gaps are filled by smaller companies like Fujifilm and Pentax.

One of these, to the dismay of many shutterbugs, is Minolta. You might not have heard of Minolta before, especially if you got into the hobby during the digital era, but you will be surprised to know just how intimately their story is intertwined with that of photographic technology and history.

Let’s take a look back and explore the annals of a camera brand that never deserved to fade from memory!

Beginnings

Minolta traces its origins back to the year 1928. Its founder Kazuo Tashima concentrated his initial business efforts around importing foreign – largely German – camera designs and re-branding them for the domestic Japanese market.

In fact, for much of this very early period, soon-to-be Minolta would use the trade name Nichi-Doku Shashinki Shoten, which translates to “Japanese-German Camera Manufacturer”.

Initially, Nichi-Doku sold a range of cameras under the “Nifca” brand (e.g. Nifcarette, Nifcasport, and Nifcaklapp), all slightly altered designs originally penned by the German group Neumann & Heilemann. These were folding cameras shooting on medium-format plates.

Eventually, following a series of labor disputes and heavy strikes around the turn of the 30s, Neumann & Heilemann grew disillusioned with the way the Japanese company was run. They decided to break the partnership to pursue their own ventures at home under greater corporate and creative control.

As a result, Nichi-Doku reorganized as “Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K”.

The First “True” Minolta Cameras

In 1933, Chiyoda revealed their design for the first camera produced in-house since the split, the Minolta. The name stood for Mechanisms, Instruments, Optics, and Lenses by Tashima, highlighting the fact that Tashima was now getting serious about the “Made in Japan” qualities of his machines.

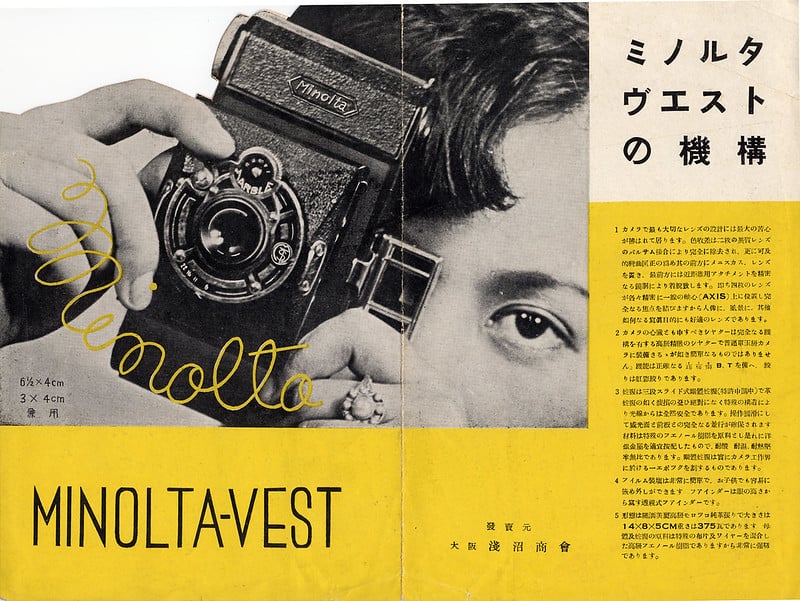

The original Minolta would form the basis for a series of folding cameras all designed and built by Tashima. Over the years, these would progressively deviate more and more from the original European cameras that inspired them. Take, for instance, the seminal Minolta Vest of 1934.

The so-called vest pocket camera, introduced by Kodak – a roll film camera that was cheap to buy, easy to use, and could fold completely flat to fit in a large pocket – was a real hit during the 20s and 30s, and Minolta sought to not just capitalize on that market, but provide real innovation.

The Minolta Vest used the same “Vest Pocket Film”, that is 127 format, as its main competitors from the United States, France, and the UK. However, instead of flimsy and often cheaply-made leather or fabric bellows, the Minolta Vest folded by means of a unique sliding box mechanism.

Imagine, if you will, a set of Chinese boxes, made out of bakelite – and attached on one side to a lens board with a shutter, and on the other to a camera body. That, more or less, is how the Minolta Vest folds and maintains its compact dimensions while being much more resilient and sturdier than its contemporaries.

Entering the Chiyoda Era

In 1937, while the Minolta Vest and its sister models were nearing the end of their production, Tashima once again restructured. Entering into a new partnership, this time with a Japanese company called Asanuma Shokai, they rebranded to Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko.

To show that they were going for a complete reinvention of their brand identity, Chiyoda Kogaku presented a slew of new Minolta camera models that year, all targeting the high-end market that had been all but ignored by the prior Nifca lineup.

Among these, quite a few ended up becoming milestones of Japanese camera development.

The Auto Semi Minolta, for instance, was one of the earliest cameras to use a coincidence-type rangefinder, where the rangefinder image was projected into the viewfinder eyepiece instead of being relegated to a separate window.

The Auto Press Minolta meanwhile tried, as the name implies, to establish the Minolta name as a major player in the field of Japanese press cameras. An evolutionary update on the original Minolta from 1934, it made major waves as the first made-in-Japan machine marketed towards journalists that could synchronize with flash.

The Quiet Birth of Rokkor Optics

While Chiyoda’s new fleet of top-of-the-line cameras did meet expectations in terms of sales, their success was soon cut short by Japan’s entry into World War II.

As with most other large industrial corporations, Chiyoda Kogaku joined the war effort by producing optics and equipment for the Imperial Japanese Navy and Air Force. During this period, they completely ceased selling their cameras to civilian customers to focus exclusively on military research and development.

Unbeknownst to the general public, it was during these grim years that one of the names most intimately associated with the Minolta name would be born – Rokkor.

The moniker, designating the highest-spec lenses and optics designed and made by Chiyoda, was initially only used for military hardware, like binoculars and gunsights. That also included optics for aerial cameras used by the Imperial Japanese Air Force.

However, after 1945 it would go on to become one of the most well-respected brands in the world of photographic lenses, finding success far beyond Japan’s borders.

The Early Postwar Years

Initially, the postwar business went ahead only slowly for Minolta. Large-scale destruction and the tumultuous nature of the late-40s Japanese economy made it just about impossible to come up with fresh, exciting ideas or radical designs.

The pro-grade press cameras and sophisticated rangefinders they had offered in the 30s had to be entirely scrapped during this period to cut down on costs.

This meant that a large portion of the new-for-1946 Minolta camera lineup were actually leftover designs dating back to the 30s. However, the company did try to give their aging folders a do-over by equipping them with all-new lenses. Namely, those shiny Rokkors that Minolta had developed for wartime use.

Among the first coated lenses put on a consumer-grade camera, they of course came with a higher price tag compared to much of the competition. Not that there was much demand for cameras in Japan at all in the immediate postwar era. In fact, sales were relatively abysmal during this time.

Still, the inclusion of Rokkor optics, at first intended as a stopgap due to the lack of supply of third-party lenses, set a symbolic precedent.

A Bold Fresh Start: The Minolta SR-2

Chiyoda’s fortunes would not change dramatically until 1958. That year, the company decided to embark on their biggest experiment yet – the release of their first interchangeable-lens system camera for 35mm film, the SR-2.

This was a pentaprism SLR with an eye-level viewfinder and instant-return mirror, only the second camera to combine all of these features after the original Asahi Pentax. The SR-2 also employed some conveniences thought of as particularly luxurious for the late 50s, such as a frame counter that automatically reset to zero when reloading, a rapid-wind lever, and a secure bayonet lens mount that had a provision for automatic aperture control.

Released with a full complement of Rokkor lenses in tow, the Minolta SR-2 came as a big surprise and wowed the photographic press. Acknowledged for its robust build quality and stunning optics, it immediately put Chiyoda Kogaku on the map as a major Japanese camera maker of high quality.

Only one extremely coveted feature of late-50s professional system cameras was missing on the SR-2: a light meter. Chiyoda tried to fix this almost immediately with the follow-up SR-1 and SR-3, which added a small mount that an external meter could be clipped onto.

However, this was a clunky solution, and barely two years later the revised SR-7 appeared on the market with a CdS meter embedded into a window on the side of the camera body.

More reliable and accurate than the more common selenium meters of the period, CdS meters ran on batteries and were generally reserved for high-end gear. Chiyoda was gunning for the top end of the market with the SR-7, and it showed.

Without a doubt, the SR-7 was the company’s most advanced and most expensive camera yet. To their great fortune, it also became by far their most successful.

So great was the upswing provided by the SR-7 and its siblings that Chiyoda decided in 1962 to formally change their name to Minolta Camera Co.

With that, a new era of Japanese camera design had begun.

Going Into Space With the Minolta Hi-Matic

Before the successor to the SR line was ready, Minolta quietly released a nifty little 35mm rangefinder packed with the latest and greatest in early 1960s camera technology: aperture-priority auto exposure.

This new camera was dubbed the Hi-Matic and became one of Minolta’s greatest financial successes lasting well into the 80s. The combination of simple semi-automatic operation and high build quality didn’t just fare well among amateur photographers, though.

One very lucky Hi-Matic, rebranded by American importer Ansco, was taken up to near-Earth orbit on John Glenn’s maiden voyage into space in 1962.

Though the idea was considered highly unorthodox at the time, Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov beat Glenn to the distinction of recording manually from space by a few months – but he used a professional movie camera to do so.

That makes John Glenn’s little Hi-Matic the first conventional stills camera to take a picture from space in human hands!

Minolta’s Worldwide Success: The SR-T

Minolta soon realized that the SLR market was on a huge upswing, spearheading the proliferation of both amateur and professional photography that was on the horizon at the dawn of the 60s.

In order to meet the demand that trend was creating, the company was very quick to announce an official successor to the SR series, the SR-T 101.

Released in 1966, the SR-T 101 was based on a modified SR-7 body with the same lens mount and some similar exterior parts. However, much of the SR-T was also redesigned from the ground up, including its radical new light meter.

On the outgoing SR cameras, you either had to rely on an external meter or use the SR-7’s built-in CdS meter. Either of these options lacked something in accuracy, as the meter read light values from a window to the side of the camera’s viewfinder.

That didn’t just introduce parallax error. The lack of any linkage or coupling between meter and aperture also meant that proper metering was a multi-step process that required the photographer to first set the meter, then read the light value, and then transfer the readings from the meter to the lens in a total of three steps.

Minolta wished to iron out all these inconveniences with the SR-T 101, and they succeeded. Dubbing their solution CLC, Contrast-Light Compensation, this groundbreaking tech allowed the SR-T to read light straight through the lens just like its prime competitor, the Pentax Spotmatic.

However, Minolta went a step further than that. Instead of copying the Pentax design – which could only read light from one spot in the center of the frame, and only with the lens stopped down – they managed to create a pseudo-matrix metering system that would assess the lighting conditions of the entire frame at once, no stopping down necessary.

That made the SR-T 101 the first SLR and the first system camera in the world that allowed for near-instantaneous metering: just peer into the viewfinder, watch the metering needle move, and select the appropriate shutter and lens aperture settings to compensate.

The Minolta SR-T 101 was not just a smash hit in terms of sales. It was a defining cornerstone of reflex camera development, solidifying the importance of easy-to-use light metering in camera design.

Increasingly marketed across a dizzying range of sub-models, variants, and trim levels, the SR-T series would keep expanding and receiving incremental updates for more than a decade. The last SR-T, the 201, would finish production only as late as 1981.

That makes it one of the longest-running camera designs in uninterrupted production ever made, whether you consider the SR series to be distinct from the SR-T or not.

Challenging the Leaders of the Pack: The Minolta XK

Fueled by the enthusiasm for their incredibly well-received SR-T cameras, Minolta immediately went to the drawing board on a follow-up camera that would be even more ambitious.

Especially as the years went by, it became apparent that the SR-T’s natural position in the SLR market was solidly in the middle of the pack.

It was too sophisticated and its Rokkor lens selection too pricey to compete in the budget segment, where the Hi-Matic felt more at home. At the same time, it lacked a certain sense of brute toughness and modularity to appeal to the high-end, pro-journalist market that was crucial during the 60s and 70s.

Thus, the logical goal Minolta set for themselves was clear. They had to sell a camera that would be able to go head-to-head with the top-of-the-line professional SLRs of the era, with no expenses spared.

The result of this enthusiastic drive to perfection was the Minolta XK, also marketed as the X-1 and XM in some countries. Released in 1973 to immense fanfare, it would open up a new chapter for Minolta and the camera industry at large.

Taking the CLC metering system from the SR-T and improving upon it drastically to give the camera full-on aperture priority auto exposure capability, the XK was loaded with the hottest technology money could buy in the early 70s.

Thanks to its SR mount, the XK had compatibility with all previous Rokkor lenses, giving it an immediately significant lens selection upon launch. It also featured interchangeable viewfinders and focusing screens, with the standard viewfinder prism head including the aforementioned aperture-priority auto exposure system.

In an era where the established rule of camera design was to create mechanically simple, yet refined modular bodies with next to no electronics save for add-on equipment, the XK stunned the press with its inclusion of several groundbreaking high-tech features.

Nobody could compete with what the XK offered in 1973. The Nikon F and F2 both had exchangeable prisms with light meters built-in, some of them even being TTL-capable, but none featured matrix metering like Minolta’s CLC or automatic exposure of any kind.

Perhaps this was the reason why Minlota boldly chose to price the XK much higher than its competition. At $790 for a basic kit including a lens, it was more than $100 beyond a comparable Nikon or Canon camera.

That’s a difference of $650 for a total price of approximately $6,000 in today’s terms!

Ultimately, it is this high price that probably kept the XK from being the great financial success and trendsetter that Minolta had hoped it would become. Another gripe commonly cited as a sales barrier was the lack of available motor drives for the XK system.

In the 70s, basically no “pro camera” accessory was as highly prized as a motorized winding grip or back, and the XK could only be ordered with an optional motor permanently attached to the body. That lack of modularity drove many members of the press away from the system and gave it a reputation of being both overpriced and undercooked.

The German-Japanese Connection

The failure of the XK system was a harsh slap in the face for Minolta’s ambitions. Still, the company’s SR-Ts and Hi-Matics continued chugging along just as before, giving the company at least a stable financial foundation to work with.

By the mid-70s however, both of these designs were over ten years old, and Minolta was facing a slump.

To both generate worthy successors to the SR-T and to continue innovating as they had done before, Minolta decided to enter into a partnership with a foreign company to encourage mutual research and development. This goal was being actively pursued well before the XK was even ready for production – a sort of fail-safe, if you will.

The decision fell on a German camera maker. Germany had been the center of camera development for much of the 20th century. But in the years following the war, stalwarts such as Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer were displaced by the onslaught of Japanese SLRs, chiefly Nikon, with whom the outdated German designs could never compete.

Minolta hoped that by entering into an agreement with one of these struggling German companies, they could help save the reputation and financial performance of both. After all, Minolta themselves started out as the “Japanese-German Camera Manufacturer”, remember?

In the end, the decision fell, and an agreement was signed with none other than Ernst Leitz GmbH, the company now known as Leica.

It might sound silly today, but the 70s were a really tough decade for the Wetzlar company.

Their M5, which tried to reinvent the classic 35mm rangefinder formula with through-the-lens metering and a geometric design, failed miserably. The photographic press was quick to spell doom for the entire brand.

Hence, it was perhaps not unreasonable at all for Leica to jump at the opportunity of a collaboration with up-and-coming Minolta. The Japanese promised fresh ideas and more economical mass-production techniques, whereas the Germans promised decades of experience in craftsmanship and construction.

The Leitz-Minolta CL

Soon, the first fruit of this unlikely marriage arrived on the scene. In 1973, only a few months after the release of the XK, Leica presented a radical new rangefinder called the CL. Instead of the horizontal focal-plane shutter of the classic Leica series, this new model used a vertically running pair of shutter curtains, designed and produced by Minolta.

In fact, the bulk of the CL, which was also sold as the “Leitz-Minolta” CL, came out of Minolta’s factory in Japan, despite the fact it carries a Leica M-mount!

Intended as a more compact, faster, and lighter alternative to the unpopular M5, the CL offered lots of convenience features like projected framelines for many focal lengths, a TTL meter, and compatibility with all M-mount lenses. A few CL-specific lenses were actually Minolta Rokkors, but the majority were still designed in-house at Wetzlar.

While the CL didn’t prove to be a gigantic success, it sent the message that Leica had hoped for: We’re back, and we’re not afraid of experimenting a bit!

The Minolta XE and Leica R3

In 1974, Minolta unveiled the XE. Featuring a much sleeker, more handsome, and more streamlined body and aperture priority AE, this was another high-tech camera for professionals with deep pockets.

Compared to the XK though, there is no denying the XE was many times more elegant. Where it completely lacked motor drive compatibility and interchangeable viewfinder prisms, it scored in sophistication, ease of use, and bombproof construction.

A majority-Minolta design, the main element of Leica cooperation in the XE’s specs was the shutter. A vertically-traveling, electronically-timed high-speed design, it was created by Leica in collaboration with another legendary Japanese company, Copal.

Seeking to expand into the SLR market, which was only growing without a hint of slowing down, Leica decided to use the XE as a base to replace its relatively unsuccessful Leicaflex SLR cameras. The result was dubbed the R3 – and surprisingly, very little apart from the Leica-exclusive lens mount and the metering system differed from its XE sibling.

Cream of the Crop: The XD and Leica R4

The late 70s proved to be a period of transformation for the camera industry. Where the start of the decade was all about sophisticated metering in large, heavy-duty modular bodies, the latter end of the decade followed a trend of downsizing.

Compact cameras, especially compact SLRs, were the status symbol to beat, largely thanks to the Olympus OM system which was breaking sales records. No longer did camera manufacturers have to compete for the very top end of the market in order to justify a flagship product – something Minolta appreciated more than anyone.

In 1977, Minolta unveiled a new top-of-the-line camera, inspired by the XE but expanding on it in significant ways. Bearing the name XD (also sold as the XD-7 and XD-11 in some parts of the world), the new camera was both more expensive, smaller, lighter, and even more pleasing to the eye than the outgoing model.

The Leitz-Copal shutter made a return from the XE, more refined and even quieter than before. The integrated TTL meter was upgraded from CdS cells to silicon diodes.

The XD also expanded on the XE by introducing shutter priority mode, making it the first camera ever to have both aperture and shutter priority as well as manual exposure.

The XD was also loaded with countless detail enhancements. For example, windows in the viewfinder displayed both selected shutter speed and aperture as well as intended values given by the meter, simplifying readout and reducing the necessity to take your gaze off the eyepiece. Instead of having an on-off switch like most cameras of the era, the meter simply self-activates and deactivates automatically by sensing the pressure of your finger resting on the shutter release.

These and other refinements made the Minolta XD a byword for elegance and build quality among those who have had the pleasure of using it.

Finally, the top-of-the-line Minolta would also receive its own matching (and removable) motor winder accessor, the Auto Winder D.

As before, Leica made use of the special bilateral agreement to produce a series of cameras using the XD body shell, named R4 through R7. While niche products by any measure, they further demonstrated Wetzlar’s ability to innovate and design cameras in tune with the modern tastes of the 70s and 80s.

Last Great Hurrah: The X-700

In 1981, Minolta added a new “X” body to its existing lineup to seal the gap left behind the last SR-Ts. This new camera, labeled X-700, advanced many of the trends started in the late 70s: automation, compact proportions, and a dizzying race towards efficiency.

Instead of a selection between manual, aperture priority, or shutter priority exposure, the X-700 offered the former two in addition to a new fully automated Program mode. Program automation was the must-have feature in consumer SLRs at the dawn of the 80s, and Minolta was playing ball.

What programmed automation did to the camera industry was open the floodgates to huge swathes of inexperienced photographers who were previously intimidated by manual exposure.

Minolta understood that this would comprise the bulk of future X-700 customers and designed the camera to be cheap and efficient to produce in large numbers. Gone were the Leica touches such as the silky film advance, ultra-silent shutter, and the luxurious metal body.

Instead, the X-700 was built using the same high-impact plastic and generous use of electronic components as contemporary offerings by Canon and others.

While the X-700 did inherit many of the XE and XD’s innovative features, a lot of them were watered down. The viewfinder information windows lost some detail, the meter was a lowlier center-weighted unit, and the shutter now ran horizontally, with silk curtains instead of metal blades.

What all these downgrades amounted to, of course, was a huge reduction in weight and price. That, and its award-winning Program mode, made the X-700 a runaway hit, becoming the best-selling of all manual-focus Minolta SLRs.

Little did buyers in 1981 know that it would also be the company’s last.

Minolta, the Autofocus Era’s Greatest Innovator

The new megaproject of the 1980s that all the major camera manufacturers were heavily researching was automatic focusing. It made sense: the 80s were very much the decade of tech and automation in photography, and having automated and downsized just about everything else about the pre-Reagan era SLR, focus was next.

Both Nikon and Pentax presented first attempts, the F3AF and the ME-F. But these were extremely clunky cameras based on existing manual-focus bodies that required special motorized lenses. Heavy, very expensive, and unsightly, they did not garner much appeal.

It was Minolta that in 1985 first presented a 35mm SLR that not only could automatically focus but also automatically advance film thanks to an internal motor drive.

This camera, called the Minolta Maxxum 7000, was the first to break with the SR lens mount which had been in consistent use on all of Minolta’s cameras since the very first SR-2 from 1958.

It also broke with established camera styling, courtesy of all that new technology. With neither a manual wind lever nor a rewind crank anywhere in sight, the Maxxum was a sleek, black beast with lots of buttons in place of knobs and levers.

All Maxxum lenses could automatically focus because the Maxxum’s focus motor was not built into the lens barrel but rather the camera body. This would be the de facto standard for generations of autofocus cameras to come.

Sudden Crisis

Minolta intended for the Maxxum 7000 to make a splash and quickly prepared follow-up models to counter the competition. The Maxxum brand grew substantially throughout the 80s and 90s, spanning dozens of models and birthing a huge lens lineup.

The capstone of the series would be the Maxxum 9, a real professional camera body featuring high-speed burst shooting, an unreal 1/12000th of a second top shutter speed, and too many electronic gadgets and features to list.

There was just one big problem. People weren’t buying them.

For all its innovations, Minolta lacked the brand recognition to go head-to-head with Canon and Nikon in the autofocus market. Worse, the arrival of AF-compatible cameras basically obliterated sales for all of the older manual focus designs.

Minolta couldn’t rely on their last-generation holdovers to keep the business afloat while they embarked on risky experiments, as they had successfully done before with the SR-T and Hi-Matic.

Instead, the autofocus era became a time of crisis for Minolta, despite the integral role that the brand played in ushering it in to begin with.

To try and overcome that struggle, Minolta ended up agreeing to a merger with fellow flagging Japanese camera manufacturer, Konica.

![]()

The Konica Minolta business survives to this day, but its camera division would not endure for long.

The End of Minolta and the Rise of Sony

Desperate attempts to save both Konica and Minolta cameras were rendered a lost cause around the turn of the millennium.

The prospect of the digital revolution required an RnD investment that the shaky conglomerate could not justify as its existing cameras remained poor sellers, so Konica Minolta decided circa 2005 to sell off its camera business entirely and focus on more lucrative endeavors, like printers and copying machines.

The company that ended up buying the remnants of what used to be Minolta was none other than Sony. Having made its name in a wide range of home electronics fields, it was natural for Sony to want to leverage their brand name to try and break into the booming digital camera world.

That they did – and not without Minolta’s help, as all of Sony’s early Alpha-series cameras utilized the so-called Minolta-Sony A-mount. This was in fact little more than the exact same mount Minolta had given its Maxxum cameras.

Many of Sony’s early digital designs would also be informed by the late ’90s Maxxum bodies and their technology.

While the Sony Alpha brand nowadays concentrates mostly on its mirrorless cameras built around the E-mount, the first 10 years of Sony’s meteoric rise to digital camera dominance could have never happened without the A-mount system and its Alpha SLT cameras, all built using Minolta DNA.

In that somewhat abstract sense, Minolta should be happy to count itself among one of the very few camera makers in history that managed to excel not only during the film era but also after the switch to digital photography.