Realism vs Pictorialism: A Civil War in Photography History

![]()

A largely forgotten bit of photographic history might be of interest: the civil war between realism and pictorialism.

Warning: This article contains some artistic nudity that may not be safe for work.

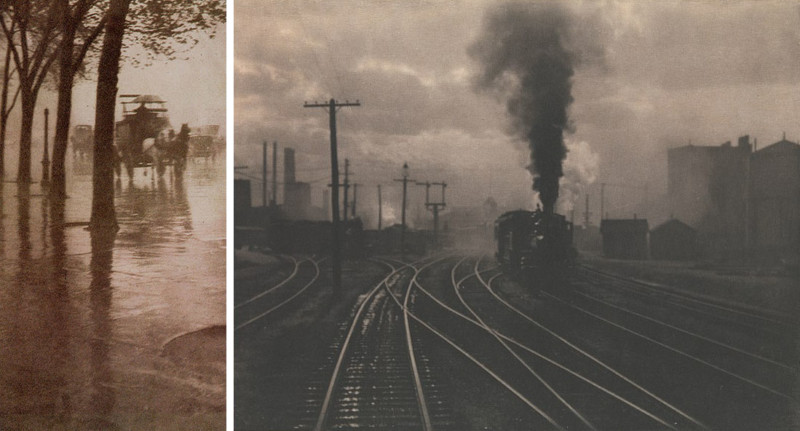

Stieglitz and his followers were typically well educated in the pictorial fine arts of the times and saw photography as an important new tool for such art. Much of their seminal work was done in the 1890s and the early days of the 1900s. Their images were usually of city scenes of the day, with people and often in rain, mist and poor light.

Photographs were typically made on orthomatic dry plates, with emulsion speed at what would be by today’s standards somewhere between ISO 5 and 10. Mood was far more important than sharpness. The lenses used were capable of reasonably sharp results when well stopped down, but often the photographers of the day did not enjoy the advantages of bright light and stable objects so that they were forced to use wider apertures, where lens performance was considerably degraded.

The photographic artists of that group and that period were and are considered to be the Pictorialists.

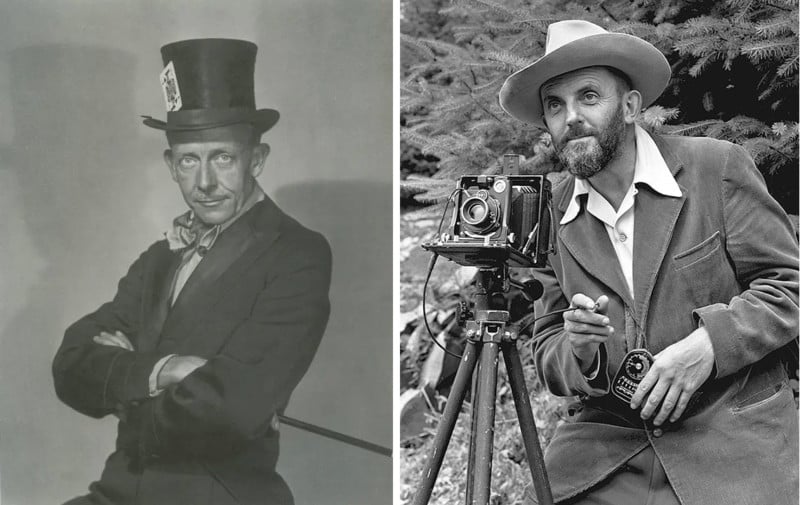

The Realists, in contrast, were dedicated to creating photographs that were as sharp as possible, typically using large format sheet film cameras and very small apertures to maximize depth of field and sharpness. Most, though not all, were landscapes, usually of the American West.

Edward Weston, in particular, did nudes and still lifes as well as landscapes. Also, though relatively expensive at the time, panchromatic films were becoming available, offering a truer rendering of color shades, all of course seen in monochrome.

The Realists believed photography to be a totally new art form, NOT a tool or technique for prior forms of art.

In their own time, the antithesis of the Realist movement was William Mortensen, who was earning his own reputation at the same time that the Realists were becoming prominent. West Coast-based Mortensen was well known as a Hollywood photographic portraitist between the 1930s to the 1950s. But he also did scenics and pictorial work that attracted a considerable following.

Mortensen’s goal in such efforts was always to create an interesting picture. To him, any technique to get it was fair game; he used fabric and wire screens, knives, brushes and pencils, soft focus, filters, grease; anything to gain the effect he sought, as well as more conventional darkroom techniques. Thus he created many very striking images that were widely admired at the time.

Ansel Adams and the Group f/64 despised Mortensen’s work and many of his techniques and got into angry and very emotional commentaries in print. Adams is on record as referring to him both as the devil and as the anti-Christ. In a very backhanded way, this was a huge compliment to Mortensen. Had his work been of lesser quality they would have ignored him instead of singling him out for their contempt.

In their defense of photography as a new and unique art form, it seems clear that the Realist’s attacks on Mortensen were in fact attacks on the whole Pictorialist school. The Realists were surely well aware that attacking the likes of Steiglitz would be at best counterproductive, whereas Mortensen was an easier and safer target, a symbol of all they despised, and time-wise, he was their contemporary.

One must wonder, none the less, just what caused such a strong reaction to Mortensen’s work? It seems unlikely that it was jealousy or envy. Rather, it seems more likely that the Realists believed he was desecrating their Holy Grail, their ideals of photographic purity. Had his images not been compelling, they could have been safely ignored.

Again, Mortensen may well have been seen as representing urban America, the rapacious perceived threat to the wilderness so beloved of the Realists. They obviously believed in a spiritual element in their love of the wilderness. Mortensen and most of his work were anything but that, and seemed to threaten the aura they were trying to develop.

A campaign to discredit and ignore Mortensen proved amazingly successful; he slipped into obscurity for many years, whereas the works of the Realist photographers gained enduring fame. When Beaumont Newhall wrote and published his book in 1978, “The History of Photography, From 1839 to the Present Day” which proved to be extremely influential, he purposely did not mention Mortensen at all, although Mortensen’s work was well known at the time and richly deserved inclusion.

Mortensen died in 1965. But in recent years interest in his work has been renewed; as people came to realize that he was, in fact, an important and very influential photographic artist, though not wholly in a classical photography sense, but also in terms of graphic art. His books have been reprinted, along with a recent biography. Some of his photographs — perhaps they would be better called “pictures” — are mesmerizing and will almost surely stay stuck in the back of the minds of viewers.

There is evidence he was to a considerable extent the developer of the Zone System, picked up and popularized by Ansel Adams, before Adams became aware of the fact that it had been Mortensen who had done the earlier work that Adams built on. But Mortensen’s legacy extends far beyond his development of exposure and processing controls. In fact, Mortensen had a considerable impact on many of the images we see today, both graphical and photographic.

It is rather ironic that most or all of the techniques of both Ansel Adams and William Mortensen can be replicated today by users of serious post-processing programs such as Photoshop or Affinity.

What is the legacy of the Realists? They certainly were successful in establishing photography as a fine art in its own right. Ansel Adams prints hang everywhere and, to a lesser extent, those of many other photographers’ do as well — a few relatively well known but most largely anonymous. In any case, most of them are certainly the spiritual offspring of the school of the Group f/64.

The civil war between the Realists and the Pictorialists is largely over, yet, the wonderful legacy of Ansel Adams still shapes landscape photography today. Color photography of landscapes became prominent, in part thanks to “National Geographic” and “Arizona Highways” magazines. Digital post-processing replaced film and darkroom magic, though some photographers still shoot film and then digitize their negatives, followed by digital post-processing. Yet, the unwritten rules of landscape photography remain to a considerable extent.

And indeed, most landscape photographers still work to emulate Ansel Adams. Here I speak particularly of his dedication to maximum sharpness and maximum density range. Roads, telephone poles and other modern artifacts are frowned on. Clouds are sometimes acceptable; fog and mist, not so much.

Pictures must be sharp corner to corner, edge to edge. A full tonal range must be included, from darkest black to the cleanest white the media can offer. Blue skies are almost always darkened in monochrome images. Human artifacts should be largely avoided; however, old examples might be acceptable, such as rotting wagon wheels, pre-World War II agricultural or mining equipment rusting in place, etc. Humans are almost always unacceptable, except possibly in pastoral settings if they are not prominent.

These unwritten rules are a bit hidebound, but they unquestionably make for beautiful photographs.

The civil war between Realists and Pictorialists is or certainly should be essentially over. Back in the day, photographers were struggling to overcome the limitations of their equipment, as well as the films available to them. It is worth noting that the films available usually had an ISO well below 25 and were orthochromatic instead of the later panchromatic films, one advantage of which allowed skies to darken instead of coming out white. Pictorialists saw photography as a new palette that would further the classical traditions of fine art. Realists saw photography as a way instead to escape the limitations of traditional fine art.

It is well worth noting that artistic painters of the day saw realized the development of photography gave them their own opportunity to escape their past of realistic or semi-realistic art and to dive deeply into abstraction.

In any case, one important aspect is that the so-called civil war was not truly a civil war, but as much an inter-generational war. Stieglitz, for example, simply did not have the much-improved tools available that had become available a generation later. In particular, the lenses available to him were, by any modern standard, terrible, suffering astigmatism, distortion, curvature of field and chromatic aberration.

Yet Stieglitz and his contemporaries created many memorable images, usually not dissimilar to the works of some of the painters of the era. One could argue that the technology available to Steiglitz made photography of the day more of an adjunct to painting fine art and that later developments opened up the potential of photography as an art form all its own.

Yet, one can look back to an earlier age — that of Matthew Brady, many of whose American Civil War photographs were relatively sharp. But the exposures for these photographs were usually at least several seconds long and that in strong sunlight.

This then begs the question: if later equipment were somehow to become available to them, would Stieglitz and his contemporaries have worked for the sharpness and depth of field of the Group f/64 style, or would they have continued their own photo-impressionism? We will of course never know.

In any case, the photographer of today has an array of tools that the photographers of the 1930s could not even have dreamed of. Beautiful color photography, computers, and post-processing, ink-jet printers, excellent zoom lenses, astounding ISOs and all at costs that are peanuts compared to the cost of a serious outfit of the ’30s.

I suggest that landscape photographers of today should no longer consider themselves as being tightly bound by the rules of the Group f/64 era. There are few photographers who have not seen the works of Ansel Adams or Edward Weston. But seek out and look at the works of Stieglitz and of Mortensen as well. They have their own validity and are very much deserving of our study and respect.

A last note: the intended scope of this article was to compare the Pictorialists to the Realists. As such, obviously much other photographic history has been ignored. My treatment of the material is undoubtedly somewhat simplistic. But the personalities, beliefs and especially the work of the above photographers shaped our views and our own work of today. They were important to our photographic heritage and deserve recognition.

About the author: Bob Locher certainly makes no claim to being a great photographer; rather, he considers himself to not be a very good one. He is not much of a speaker either, and does not have his own YouTube Channel, nor does he do Photographic Tours. But, he has been in the photographic hardware industry most of his life, fancies himself as something of a writer, has opinions and is not afraid to express them. He loves photography, values technical quality and is indeed a pixel-peeper. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Locher has written over 50 magazine articles as well as two books. You can find more of his work and writing on his website.