What is a Rangefinder Camera?

In the photographic arms race, mirrorless systems are on the rise, having pushed DSLRs into the history books. But, just as film isn’t dead, neither are rangefinders. This seemingly obsolete design remains sharp, fast, and challenging enough to suit even the most confident photographers.

Table of Contents

What is a Rangefinder?

Rangefinder cameras use a double-window system that provides extremely accurate manual focusing.

A rangefinder camera has a viewfinder window with bright lines that denote the frame of the film or sensor, which the photographer uses to compose the shot, and it has a rangefinder window a few inches beside it. The rangefinder window projects a separate image onto the viewfinder image, and when these two images line up, the lens is perfectly focused on the subject.

To focus with a rangefinder camera, a photographer simply adjusts the lens’s focus until the focusing patch is aligned with the main viewfinder scene.

Besides offering tack-sharp focus that does not rely on electronics to function or to decide who’s the subject, rangefinders also help photographers with depth of field. Historically used by people such as cartographers and sailors, the rangefinder employs triangulation to gauge a subject’s distance, or range.

After properly focusing on your subject, you can look at your lens’s distance scale to see the focusing distance. Knowing exactly how far away your subject lies will let you set the aperture, using the depth of field scale, to achieve a shallow or deep depth of field. Rangefinders make you work a bit, think a bit, but with time the process becomes second nature.

Novices can pick up a rangefinder and shoot, but the camera type especially benefits experienced photographers. The quality of a rangefinder remains high. Several factors explain why.

Accurate focus aside, rangefinders achieve excellent results thanks to the prime lenses they require. Zoom lenses don’t work because a constantly changing focal length cannot couple with the rangefinder. Prime lenses, however, are known for generally producing higher image quality than zoom lenses.

And since rangefinders do not use a mirror (to project the image from the lens into the viewfinder), the lens rests closer to the film plane or sensor, which creates a sharp, defined image. The absence of a mirror lends other benefits to the rangefinder system, as described below.

A Brief History of Rangefinder Cameras

Early non-coupled rangefinder cameras used a separate rangefinder system that allowed photographers to determine the correct focusing distance to their subject and then transfer this calculation to their camera lens’s focus ring.

Rangefinder camera usually refers to camera bodies with coupled rangefinders, and this began with the Kodak 3A Autographic Special in 1916.

But they took their biggest leap forward as Leica 35mm film cameras. Early Leica cameras popularized the use of rangefinder add-ons, but the legendary M3 first combined the viewfinder and rangefinder in 1954: the M stands for messsucher, the German word for viewfinder-rangefinder.

The Leica M3 was a huge commercial success, with over 220,000 units sold during its production run through its 12-year production run ending in 1966.

Other brands that found success in the heyday of film rangefinders include Nikon, Canon, Kodak, Zeiss, Contax, and Argus.

The rise of the single-lens reflex (SLR) camera — with revolutionary models such as the Nikon F in 1959 — and autofocus lenses ended the rangefinder’s dominance in photography, but those new technologies did not cancel the rangefinder altogether.

Amateur rangefinder models still found success in the 1960s, and Japanese brands such as Canon, Fujica, Olympus, Yashica, Ricoh, Minolta, and Mamiya still produced popular fixed-lens 35mm rangefinder cameras that survived for a time before autofocusing compact 35mm cameras stole their thunder.

With the ubiquity of the electronic viewfinder, some may consider today’s rangefinder system obsolete. Yet newcomer camera companies like Pixii are developing state-of-the-art rangefinders, and Leica’s new M11 sells for more than any other prosumer full-frame digital camera body.

The rangefinder’s benefits still outweigh its disadvantages, keeping the system relevant a century after its invention.

In 2010, Fujifilm unveiled the Fujifilm X100, an influential camera that started the company’s X100 series and led a wave of digital cameras inspired by vintage camera designs. Although the camera series is designed to look and work like a rangefinder camera, the cameras are not technically rangefinders.

The X100 series does feature a direct optical viewfinder like rangefinder cameras, but the focusing system does not use a rangefinder-style system for manual focusing. Starting with the X100T and in subsequent models, Fujifilm introduced an “electronic rangefinder” feature, but this is simply a small EVF display in the corner of the optical viewfinder that provides an enlarged view of the patch the photographer is focusing on — focusing does not involve lining up two patches like in a true rangefinder camera.

The faux rangefinder system “makes manual focusing while using the optical viewfinder much easier, and more like a mechanical rangefinder,” Fujifilm says.

Benefits of Rangefinder Cameras

There’s a lot to like in a rangefinder. The focus, the feel, the simplicity, the experience: the list goes on. This isn’t to say that an SLR or a mirrorless digital camera pales compared to a rangefinder. Each camera type offers its advantages, and for a classic or mechanical photographer, the rangefinder hits a lot of notes.

Accurate Focus

Perhaps the rangefinder’s single greatest attribute is its unflinchingly precise focus. It must be mentioned that in the early days of the SLR, before autofocus lenses, the viewfinder screen showed a fuzzy overall scene until the lens focused on its subject. Compare this to the rangefinder’s small rectangle in the middle of the viewfinder. Here, in this rectangle, is where focus becomes clear.

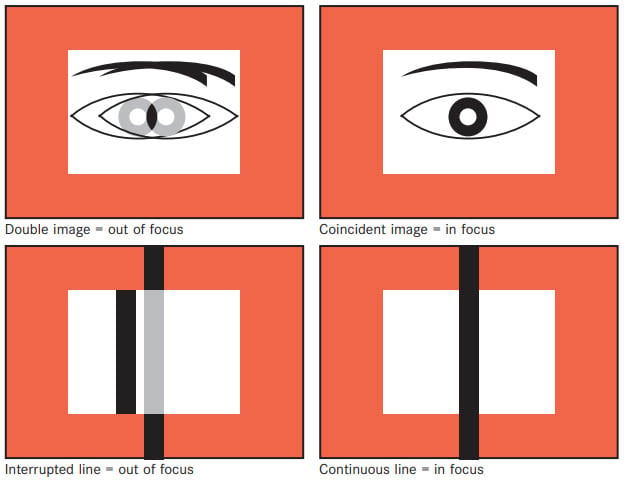

The human eye is better at detecting double and split images than it is at discerning between an absolutely and a nearly sharp image. Rangefinders make focusing easy. If you’re focusing on a telephone pole, it will be in focus when the pole makes a continuous straight line from the outer area of the viewfinder, down through the central focusing rectangle, and again into the viewfinder’s outer area. This is called split-image focusing.

For a subject like a person’s head, the viewfinder will show a fuzzy, low-contrast duplicate head when out of focus. When the focusing rectangle shows one fused, brilliant image, the head is in focus. This is double-image focusing.

Photographers can check split- and double-image focusing for a subject in order to be extra sure of correct focus. One trick for focusing on a subject with horizontal lines is to turn the camera vertically for focusing, then return it to a horizontal position for taking the photo (assuming a landscape orientation is desired). With no autofocus, the lens will naturally hold focus unless you move it.

Rapid Focus

By using these focusing techniques, rangefinders work well in poor light, and they accommodate bad eyesight. Detecting poor focus is relatively easy when something like a telephone pole doesn’t line up through the entire viewfinder, or when a person seems to have a faint double image lingering next to it, one that moves around when you move the lens focus ring.

For this reason, rangefinders also allow for relatively fast focusing. With a short amount of practice, it’s easy to tell if the lens focus ring must move right or left to move the telephone pole or figure into alignment. Many aspects of photography become faster once the computer or machine gets out of the way.

Rangefinders are popular for street and feature photography, but they’re also useful for photographing children, animals, and sports. One reason is the stable focus. Rangefinders allow you to easily focus on a spot, wait for the subject to pass by that predetermined place, and then quickly snap a frame.

Seeing Beyond the Frame

A rangefinder’s viewfinder shows more than just the frame it puts on film or sensor. Framelines within the viewfinder show what will actually be captured in the resulting photo, but there is also additional space that provides a wider view of the scene for context.

This feature of rangefinders lets the photographer watch for action that is about to enter the frame and release the shutter when the moment is right. With an SLR camera, on the other hand, what you see through the viewfinder is roughly what you will get in your resulting photo, so a photographer will need to take their eye off the viewfinder or open their non-viewfinder eye in order to see the wider scene being photographed.

No Mirror

Granted, the absence of a mirror made more impact before mirrorless cameras, especially now that the DSLR is in a tailspin. Compared to a single-lens reflex camera, a rangefinder feels calm when clicked and it makes little noise. This allows for shooting at slower shutter speeds because no mirror means less camera shake.

Quiet shutters keep you discreet on the street, in the subway, or wherever else you’re inconspicuously snapping photos of unsuspecting subjects. No mirror also lets the lens sink into the camera body more, putting its rear element closer to the sensor or film plane. This makes for an overall sharper image.

Prime Lenses

The rangefinder’s reliance on prime lenses also helps deliver superior image quality, due to the prime lens’s simpler design and concentrated precision. Also, prime lenses are small because they lack autofocus motors and components. This makes the rangefinder set-up especially good for travel and keeps a photographer discreet when doing street or even portrait work.

Compact and Reliable

Comparing a rangefinder to a single-lens reflex becomes harder as the DSLRs disappear from the market, but back in the day a rangefinder was noticeably smaller and lighter than a camera with a moving mirror inside of it. Today, rangefinders continue to weigh less than many mirrorless cameras, and they fit better in your pocket. The latest mirrorless cameras rely on technology and autofocus to please users, which means they need room to fit more electronics.

Digital rangefinders don’t need to be bulky. In fact, that contradicts their purpose. Rangefinders inspire simplicity in photography. Less computational technology is more, for rangefinders. Simple usually translates to reliable, and in film rangefinders, this can extend as far as a purely mechanical camera that doesn’t even need a battery. The re-released Leica M6 film camera, for example, only needs a battery for the light meter but can operate fine without it. This can be great in extremely cold conditions and on long, remote travels.

Different Shooting Experience

Accurate focusing is one thing. The feeling you get while photographing is another — is this not the most important aspect of photography? Thanks to their inherent simplicity, rangefinders reduce photography to its essence.

Rangefinders take you back to the basics of photography. They let you concentrate on making photos without having to overthink. Forget excess buttons and beeps. Henri Cartier-Bresson made photos better than we will ever achieve, and he used a rangefinder, no autofocus.

Drawbacks of Rangefinder Cameras

Alas, no camera type is perfect (which is why it’s fun and wise to own or practice with many). Rangefinders are certainly not for everyone. They can be a pain. Like any tool, they come with limitations. Rangefinders can definitely restrict your photography. How?

Parallax Error

The viewfinder window on a rangefinder sits above and beside the lens. What you see is not what you get. This means you can inadvertently cut off parts of your subject.

Parallax is worse at close range. Some rangefinders, like the Leica models, compensate for this by shifting the viewfinder’s bright lines — the markers that determine the actual area of the film or sensor’s frame — as focus changes from near to far, but not all cameras offer this assistance.

At large distances parallax is insignificant. But close-in it becomes important and must be accounted for. In the digital world, parallax can be remedied with live view or with instant review, but with film, the photographer had better get to know his or her camera well and make necessary adjustments to composition.

Difficult and Challenging

Rangefinders make you do a lot of the photographic work. Beginner photographers can learn much from a rangefinder, but the learning curve is steep. Rangefinders will improve any photographer’s technical chops, but they require an investment of time. Manual focus, no zoom, film, a basic light meter, parallax: rangefinders present myriad obstacles.

Apart from these challenges, rangefinders, especially the film versions, offer shutter speeds that aren’t quite as fast as a single-lens reflex camera: some rangefinders top out at 1/1000 or even 1/500. With film and its fixed ISO, this can lead to serious sacrifices of aperture and thus depth of field.

Rangefinders focus easiest with shorter focal length lenses. However, macro lenses do not work well with a rangefinder, and neither does anything over 135mm, when focusing becomes a nightmare. Even a 90mm lens can be hard to focus when your subject is close or moving. The lack of zoom options is limiting, especially when you budget for a quiver of focal lengths to replace a standard zoom.

Few digital rangefinders exist, and compared to entry-level (or even top-of-the-line) DSLRs and mirrorless, they are spendy. Plenty of affordable, even outright cheap, rangefinders do exist in film, as mentioned below. But rangefinders require precision alignment to work properly, and cheaper options might not focus so sharply, or they might easily fall out of alignment.

The above reasons suggest why most professional photographers today work with advanced camera systems — mirrorless bodies that accept autofocus zoom lenses and come complete with onboard mini-computers. But photography is also art, and what fun is a camera that tries to out-smart and out-maneuver you, that thinks it knows what you’re trying to do? This is one reason why rangefinders have survived the last century of photography.

Some Rangefinders to Consider

Film Rangefinders

Olympus RC. This extremely compact camera makes no fuss. It has auto and manual exposure settings but remains completely manual. A battery is used for the light meter, and it has a reputation for durability. The Olympus RC features a 42mm f/2.8 lens.

Hasselblad XPan. The Hasselblad uses regular 35mm film to make 35mm photos, but it also features a panoramic mode to capture images in 24 x 65mm: two 35mm frames together make this cool panoramic frame. The XPan is ruggedly made of titanium and aluminum, and it works with interchangeable lenses.

Fuji GW690iii. Also known as the Texas Leica, due to its size and weight, this medium format rangefinder

nonetheless takes fine 6 x 9cm (medium format) photos. It features an EBC Fujinon 90mm, f/3.5 lens. No light meter and no battery mean no nonsense and a long life for this classic film camera.

Canonet. Quiet, small, and unobtrusive, the Canonet is also a bargain. But its 40mm F1.7 lens is perfectly

capable of taking sharp, contrast-rich photos. The viewfinder offers parallax compensation, but the light meter’s mercury batteries are no longer available. Still, a favorite of many film shooters.

Digital Rangefinders

Pixii. This little-known brand comes from France. It has a 26-megapixel APS-C BSI CMOS sensor, uses the Leica M-mount lens system, and offers a distinct monochrome shooting mode. The Pixii has an interactive optical viewfinder which includes a rangefinder focusing rectangle but also shows key information like exposure speed or exposure compensation.

Leica M11. The king of rangefinders continues to bear the Leica name. Evolved directly from the M3, the new M11 includes an array of high-tech features including a pixel-shifting, full-frame 60-megapixel BSI CMOS sensor. Its viewfinder has a focusing rectangle and arrows to tell you if your shot is over-, under-, or “correctly” exposed. This is pure rangefinder technology, at a luxury mirrorless price.

Conclusion

Using a rangefinder camera provides a photographer with simplicity, pleasure, limitations, and challenge. They might just be the love-hate camera. Naysayers aside, the rangefinder is beloved for its classic approach to photography and its brilliant focusing system, among other attributes.

Good photography should not be as easy as point and shoot, rangefinder aficionados will argue. While the entry cost for a digital rangefinder may exceed most budgets, a quality film rangefinder can set you back a few hundred dollars. The only way to know if rangefinder photography is your thing is to try one, which also provides a good excuse to shoot film. Just as with film, practicing with a rangefinder will make you a stronger photographer. That’s reason enough to pick one up.

Image credits: Header photo by Hannes Grobe and licensed under CC BY 3.0.