Cottingley Fairies: The Photo Hoax That Fooled Kodak and Arthur Conan Doyle

![]()

Just after the Christmas of 1904, a group of lucky children nestled into their seats at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London for a night of whimsy and wonder. There, they witnessed the first adventure of a boy who could never grow up, clad in autumn leaves and cobwebs. Their eyes expanded with delight as he entered the room of children just like them, on a mission to retrieve a friend.

“Tinker Bell, Tink, are you there?” he whispered.

A nearby jug lit up on the stage, to the glee of all present. For the youngest among them, this flickering light, this Tinker Bell, was more than a trick of a crafty stagehand. To them, she was real. As the light darted this way and that across the proscenium, they giggled and cooed. Later that evening, the boy on stage, Peter Pan, would implore those in attendance to save his glistening friend by simply believing in her. He needn’t have even asked — they already did.

![]()

A little over a decade later, many of those same children were gone, their lifeless bodies pressed into foreign mud. Like Peter Pan, they would never get the chance to completely grow up. The first World War had arrived and England was suffering. Food shortages were widespread, and rationing was on the way. Loved ones were lost or wounded, homes broken, and the nation had spent a massive percentage of its GDP to participate in the conflict. It was a dark time, and no one was certain how, when, or even if it would end.

One life upended by the Great War was that of Frances Griffiths, age 9. In 1917, upon her father’s conscription into service, Frances and her mother left the British colonies of South Africa and settled in Cottingley, West Yorkshire. At a time when the pall of death hung low across the nation, the rolling hills and forests of Cottingley offered a kind of green therapy.

With her 16-year old cousin Elsie Wright as a companion, Frances explored, escaped, and — most importantly for any child — she played. The girls played so much, in fact, and with such abandon, that they suffered frequent scolding from their parents upon arriving home late and dirty. Eventually, exhausted from the correction, Frances offered up a straightforward explanation: It was not her fault she stayed gone so long; she was simply distracted by the forest’s many fairies.

![]()

As one might imagine, this excuse found little purchase with the adult members of Frances’s family. Elsie, however, assured their parents that Frances was telling the truth. There were fairies in the forest, and, with the use of Frances’s uncle Arthur’s camera, the two could prove it. Armed with his W. Butcher & Sons Quarter-Plate Midg camera, Elsie and Frances set off into the woods.

Within the hour, the pair returned, proud as they could be to have proven their innocence. Arthur, an amateur photographer, made use of his darkroom and developed the image. There, clear as day, was young Frances, stifling a grin as a series of fairies danced before her on a log.

Now, Arthur was no fool, and knew his daughter, Elsie had both an interest in and a knack for photography herself. Though he could not prove how they had done it, he was certain of their mischief. He suspected the answer was as simple as paper cut-outs displayed before the camera. To allay his doubts, the girls took yet another photograph. In this one, Elsie was directly interacting with one of the mythical creatures — not merely a fairy, but a gnome.

Arthur was as impressed with the initiative as he was incensed by the impudence. While the girls were away, he searched their living spaces and the creek bed itself for proof of their ruse. Though he turned up no evidence, Arthur, not being a child, continued his disbelief of the sprites and restricted the girls from further use of his camera. Elsie’s mother Polly, however, proved to be a different sort of case entirely.

In the late 1800s, a new movement with very old roots had begun popping up across the globe. The Theosophical Society, as it was known, was a remarkably forward-thinking and progressive movement for the time. They focused on the universal brotherhood of humanity, without distinction of race, creed, or color. They encouraged the study of religion, philosophy, and science. Unfortunately, their teachings and beliefs did not stop there. Their third tenet — “to investigate the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man” — seemed positive enough on its face, but in practice led to some rather far-fetched views. Of note was the belief that human evolution was something to eventually be harnessed and controlled, unlocking what some would regard as mystical superhuman powers. Members of the society viewed its role as one of a guide, directing humanity on the best way to manage its evolution and ascent.

![]()

Polly Wright was a frequent attendant of events of the Theosophical Society. By her time, the group had become a full-fledged progenitor of modern-day New-Age spirituality, complete with its own attachment to Hollywood and trend-setting. When Polly saw the rudimentary fakery of her daughter and niece’s photographs, she did not enjoy the same skepticism as her husband. No, for Polly this was indeed a sign. Fairies, if they exist, must surely represent the cosmic evolution of mankind, a flashing billboard on the road away from a globe consumed by war and death.

Less than a year after the end of the Great War, in a nation that had lost over 700,000 of its people, where optimism was rationed as tightly as food, Polly Wright arrived at the local Bradford Theosophical Society for a lecture on fairies. Undeterred by her husband’s stern rationalism, she had brought with her what she believed to be, as we would say today, “the receipts.” What was so easily dismissed as the winking excuse of two children for their play was, in this room, at this time, welcomed wholeheartedly as proof of a grand design by credulous adults.

One of the adults most enthused by the photos was Edward Gardner, a fervent supporter and member of the Theosophical Society. Gardner went so far as to have the photographs authenticated by photographic expert Harold Snelling. Snelling, for his part, only validated that the images contained only that which was in front of the camera. The matter of what they were, he left to others. He was, after all, only an expert of photography, not mystical creatures.

Emboldened, Gardner took the images and began giving lectures on them in London. He ensured these images were shared at the Society’s yearly conference in Halifax. While skeptics, even among the Theosophists existed, many were drawn to Gardner’s forceful view that these fairies were no mere trick, but supernatural proof that the cosmic metamorphosis of mankind was already underway. More than mere rabble bought in. Quite the contrary. The fairy hoax brought in high society types of all varieties, including world-famous authors like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

![]()

While Doyle is most known for his creation of the world’s greatest detective, Sherlock Holmes, his own powers of deduction were far less keen or rooted in logic. He was a devoted spiritualist, on a constant journey throughout his life for something divine, something ecstatic, something beyond reality — something true. Reality, after all, was not so pleasant at the time. Doyle, like so many of his countrymen, had also lost a son to the insufferable Great War.

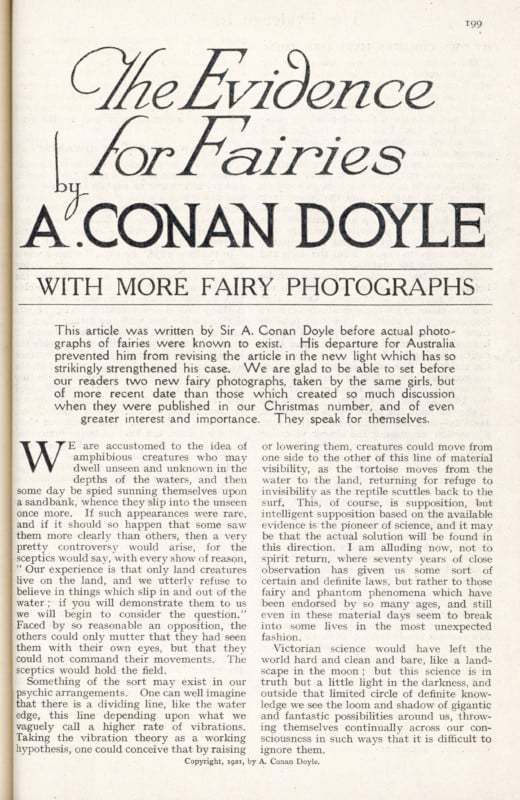

Doyle first became aware of the Cottingley Fairies through an article in the spiritualist publication Light. In a matter of coincidence, which he perceived as something more portentous, this occurred while Doyle was working on an article about fairies for the Christmas edition of the Strand magazine. He was so taken by the girls’ photographs and the serendipity of discovering them that he requested the use of them for the piece. The Wright family was quite star-struck and quickly agreed, though refused any fee.

Doyle and Gardner then sought further confirmation for their beliefs, going so far as to reach out to Kodak for the best analysis possible. The images were pored over by the company’s expert technicians, and, while they concurred with Snelling’s prior opinion, Kodak itself refused to certify authenticity. Gardner’s view of this denial was conspiratorial, accusing the company of anti-spiritualist bias. The unofficial agreement was enough for Doyle, however, and his obsession only grew.

Doyle sent Gardner to Cottingley along with two W. Butcher & Sons Cameo folding plate cameras and twenty-four camera plates. There, Gardner beseeched the Wrights to allow the girls to take more photographs and collect more evidence of these ethereal beings. The Wrights obliged. Elsie and Frances were in a predicament. With all this added attention, they were forced to develop new rules for the fairies in order to maintain the illusion. They told the adults the creatures would only emerge for children, and only if they were fully alone.

![]()

Twenty years prior, adults in the Duke of York’s Theatre had convinced children that a flickering light was a real fairy worth believing in. Now, two young women were forced to stage elaborate photographs, tricks of paper and light, to confirm the fantastical beliefs of grown people.

And it worked. The young women produced a set of new fairy pictures that made Gardner and Doyle giddy. In correspondence, Doyle gushed to Gardner:

“When our fairies are admitted, other psychic phenomena will find a more ready acceptance.”

He also expressed his sense that this was only confirmation of messages he had received from numerous seances.

Doyle carried this energy into his article, headlined, without a hint of caution, “FAIRIES PHOTOGRAPHED: AN EPOCH-MAKING EVENT.” Within the piece, Doyle passionately, foolishly argued that the images were credible, and their capture was a moment of divine heraldry. Criticism was immediate, though hardly merciless. Because of Doyle’s high status and goodwill for his work, most responded with a sort of polite bemusement or second-hand embarrassment that Doyle had been so taken in. It mattered little to him, however. Thanks to his imprimatur, a whole new segment of the population now accepted this strange fantasy without question. There is no greater fuel for a fiction presented as truth than the credence of celebrity. The nation allowed itself, after a grueling multi-year war, to have loud, angry arguments over the dinner table about the existence of magical sprites signaling a New Age of Man. In terms of the stakes they had been operating under, this was both forgivable and, in some sense, welcome.

The Cottingley Fairies yielded decades of grist for the twin industries of New Age belief and conspiracy media. Doyle himself died believing the myth he so advanced, even going so far as to write a follow-up article and, later, a book on the topic. Throughout the decades, a journalist (or muckraker) would find a new fascination with the tale, track one of the girls down and begin the cycle anew. Despite being adults who could see the ridiculousness of their childhood excuse-turned-whirlwind, Elsie and Frances refused to admit the deception. It was not until 1983 that they finally came clean — though even then Frances claimed one photograph, their fifth, had been entirely real.

![]()

But fairies are not real. The girls had merely used simple paper cutouts, traced, repurposed, or redrawn from the images of the books and magazines they had access to. Arthur had been right all along. In a twist of supreme irony, the girls had traced illustrations from a particular book of folklore that, within its pages, contained a short story by none other than… Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself.

One is left to only imagine how Doyle would have interpreted this information. Would he have accepted it as conclusive evidence of his naivete, or would the supreme coincidence have been merely one more glowing arrow pointing toward his cosmic fantasy? Evidence surely points us to the latter, but what is most remarkable about this, as with so many hoaxes that find traction in the mainstream, that survive despite debunking after debunking, is that the people most apt to engage in conspiracy and fantasy are often, whether they know it or not, the most acutely aware of the pain of reality as it is. Nowhere is this clearer than the close of Doyle’s first article.

“The recognition of their existence will jolt the material twentieth-century mind out of its heavy ruts in the mud and will make it admit that there is a glamour and mystery to life.”

In his effort to justify his belief in silly fiction, Doyle did more to explain the human need for that fiction than he himself realized.