Laowa Argus 25mm f/0.95 APO Review: Excellent Lens with a Caveat

![]()

Venus Optics has introduced yet another unique lens to the market: the Laowa Argus 25mm f/0.95 APO for Micro Four Thirds. As a long-time user of the Micro Four Thirds system, I jumped at the opportunity to test drive this lens after I heard “0.95” and “APO” in the same sentence.

Venus Optics has, over the past few years, proven itself to be one of the most daring and interesting lens manufacturers in the world, entirely unafraid to venture into very niche territory. From incredibly unique lenses like the 15mm f/4 Macro Shift lens, to the niche 24mm f/14 2x Macro Probe, to numerous “Zero-D” wide-angle lenses, to a plethora of 2x Macro APO lenses, and so much more, Venus Optics has proven itself capable of delivering excellent image quality at a low price, while offering lenses that no one else on the market does.

I will say upfront, I am not a photographer who obsesses over super shallow depth-of-field — most of my work is stopped down and I find arguments over f/1.2 versus f/1.4 versus f/1.8 lenses bafflingly inane. With that said, it’s hard for me to resist the potential that an affordable f/0.95 lens offers for low-light and video work, and impossible to resist one with an APO tag.

![]()

This isn’t the first f/0.95 APO lens from Venus Optics — that title goes to the Laowa Argus 33/0.95 CF APO for mirrorless APS-C cameras. Both these lenses offer a 50mm full-frame equivalent field of view (diagonally, with different aspect ratios) with the 33mm equivalent to f/1.4 on full-frame and this one giving us f/1.9 equivalence (in terms of depth-of-field and total light gathering). This is likely no coincidence — fast 50-ish equivalents are much easier to design than other focal lengths while still yielding great image quality and a reasonable size.

Build Quality and In-Use

The lens body is a nicely robust (and seemingly completely) metal design; it certainly feels as hefty and solid as one could possibly hope for from a sub $500 lens with such ambitious specifications. The focus ring is pleasantly smooth, with a long focus throw (about 300 degrees). Most of this is in the first three or so feet, with three feet to infinity being covered in about 45 degrees. This is good and bad — a fast lens like this will require extreme precision in focusing on the closest distances and a longer throw certainly helps but also means very quick focus adjustments are quite difficult.

Oddly, the aperture ranges from f/0.95 to f/11 — I haven’t seen a lens that doesn’t go to f/16 or lower in a long time. This isn’t really an issue (you’d be well past diffraction at f/16 on M4/3), just a peculiarity.

![]()

Unfortunately, the aperture ring desperately needs to have better damping. Even straight out of the box, the ring is very easy to move, and it often resulted in accidental changes. All my cine lenses, from numerous manufacturers, have significantly stiffer T-stop rings and there’s no reason this can’t too — quickly adjusting the aperture would actually be more critical with video work than stills, and yet this is looser than any lens (cine or otherwise) I’ve ever used. For stills, however, you want something that stays where you set it, and there were far too many times I found myself stopped down when I had set the lens to f/0.95.

The main issue, aside from the freeness with which it turns, is that the aperture ring stops down from the left. So, if you are focusing with your left hand, and the lens is at f/0.95, a mere bump of the ring will turn it. If it stopped down by turning counterclockwise, instead of clockwise, this wouldn’t be an issue. Eventually, I just decided to wrap a piece of electrical tape around it to hold it in place. This is easily the most unfortunate flaw with this lens and honestly, it is so bad that I’d suggest Venus Optics redesign the lens’s aperture ring with improved damping for production moving forward.

![]()

The choice to use a declicked aperture ring isn’t new for Venus Optics; many of its lenses have gone in that direction, which is a little strange to me given that the company also produces cine versions of many lenses. Why not save the de-clicked aperture ring for the geared cine version? Not to mention, some Laowa lenses — the full-frame Laowa 45/0.95 Argus and Laowa 35/0.95 Argus, for example — have click stops and feature a de-click lever (like the Voigtlander Micro 4/3 lenses, which use a shift and twist mechanism, or the Zeiss Loxia/Milvus lenses, which use an adjustment screw on the mount bayonet). Why Venus Optics decided not to do that with this lens, I’m not sure.

The lens comes supplied with a nice, sturdy hood, which is easily reversible for more compact storage. I applaud the build quality of the hood; at first, I thought it was part of the lens body (it comes out of the box in its non-reversed position). It feels strong enough, and is small enough, that one could easily leave it in place and not see much of an impact on the space in your bag nor worry about it snapping off.

![]()

This is especially good because, as I learned, the hood is a must-have if you’re shooting in the sunny outdoors or anywhere with a strong light source outside the periphery of the frame.

![]()

Unfortunately, the lens has no contacts for CPU data — you must be sure to input the focal length in the camera (for IBIS) and there is obviously no metadata for the F-stop nor in-camera corrections. It also means you’re likely focusing at your shooting aperture.

Optical Design

The Argus 25mm is not a simple design: there are 14 elements positioned in eight groups. Three of those are Ultra High Refraction, along with one Extra-Low Dispersion and one aspherical element. The presence of an aspherical element promises improved image quality, though the correction of spherical aberrations via aspherical elements can sometimes (though certainly not always) result in harsher, more nervous bokeh. Sometimes you can’t get everything.

![]()

Like most high-quality 50-ish equivalent lenses, the optical design is a heavily modified double Gauss (“Planar”) formula. It also boasts a 0.17x magnification factor, which roughly translates to a very useful 1:3 FF-equivalent magnification ratio.

The diaphragm consists of nine rounded aperture blades for, hopefully, round and smooth bokeh at any aperture.

![]()

I was supplied with the above MTF (modular transfer function) chart, which shows the (theoretical) performance wide-open, and it certainly does not promise disappointment. Something interesting to note here is that Venus Optics uses 20 and 60-line pairs per millimeter in its MTF chart! Most others only use 10 and 30 lp/mm, and sometimes 40 lp/mm.

This chart certainly heightened my expectations.

Image Quality

Note: All sample images were shot at f/0.95 unless otherwise noted. None of the images have had any vignetting or distortion adjustments.

And now the big question for any lens: how does it perform optically? With an extremely fast f/0.95 aperture, an ambitious APO tag, and an impressive theoretical MTF, it has a lot to live up to.

Sample images were shot on the fantastic OM System OM-1, which I reviewed for PetaPixel, as well as the new Panasonic GH6. Keep in mind, with the higher base ISO of Micro Four Thirds cameras (ISO 200 for most, except the GH6 which is ISO 100) plus the extremely fast aperture, you will easily exceed the camera’s maximum 1/8,000 mechanical shutter speed in the daytime. Thankfully, the OM System OM-1 has a very fast stacked sensor readout and great electronic shutter implementation up to 1/32,000, but for other models, you may need to resort to ND filters if you want to shoot wide open in the daylight depending on your subject.

Sharpness and Chromatic Aberration

Let’s start with the positives, of which there are many. The lens is incredibly sharp wide open — with some caveats.

And it’s not just the center: resolution remains very high right into the corners.

This is remarkable performance for an f/0.95 lens of any price. There is some astigmatism as we move away from the center and microcontrast — the ability to resolve discreet transitions of high-frequency detail — loses some of its bite in the outer periphery, but all in all, this is extremely impressive for a lens of this speed and especially its price.

Believe it or not, it doesn’t end there. Lateral or axial chromatic aberration — at any aperture, even under situations designed to provoke such aberrations — is almost non-existent. There is some very light purple fringing in some circumstances, but that’s about it. The Laowa 25/0.95 wears an APO tag and it deserves it.

Global contrast is somewhere in the middle, while microcontrast is surprisingly great wide-open. By f/1.4 and especially f/2, microcontrast becomes consistently excellent across the frame. Though, again, this is with some caveats to be discussed.

Focusing is very easy thanks to the excellent focus peaking of both the OM System OM-1 and Panasonic GH6. Since we’re not shooting with the true depth-of-field of a 50mm lens, focusing is a little more difficult (the deeper the DOF, the harder it is to discern the perfect plane of focus), so punch-in magnification is generally the best way to go for critical focus.

The transition between in- and out-of-focus isn’t as sharp as I’d like it to be (which also makes focusing more difficult). Rather than the crispness that we see with Leica ASPH, Zeiss Otus, Nikkor S, Voigtlander APO, or Sigma Art lenses — where the lens “slices” the scene into very distinct planes of focus — the Laowa 25 displays more of a gradual roll-off from in- to out-of-focus. This is similar, though with much better sharpness, to fast vintage primes, like a Minolta MC 58/1.2 or Nikkor 50/1.2 AI-S.

The reason for this is what we’ll get into next.

Spherical Aberration

![]()

Remember what I said about aspherical elements? Well, no need to worry about that — the Laowa 25 APO displays a very significant amount of spherical aberration (SA) wide-open. This presents as a sort of “blooming” or “glow”, particularly around high-contrast edges (e.g. a tree against a bright blue sky, lit signs at night). In short, this is caused by optical flaws where the peripheral light rays don’t converge at the same point as those in the center — basically, not all of the light focuses at the same point on the sensor, as it would in a theoretically perfect lens.

Spherical aberration (SA) is a type of monochromatic aberration and is not uncommon for very fast lenses; only highly-corrected (read: expensive) lenses like the Leica Noctilux 50/0.95 or Noct-Nikkor 58/0.95 display little or no SA. It’s also the only type of aberration that uniformly affects the image; it’s no better in the center than it is at the edges.

Because SA is caused by the most lateral rays, stopping down quickly reduces the effect of SA as it cuts out those marginal rays of light. In the case of the Laowa 25mm APO, the spherical aberration improves quite quickly when stopping down — even f/1.1 shows a noticeable improvement, and by f/1.4 to f/2 it isn’t really an issue.

This doesn’t always happen, but after some time using the lens, you can get a feel for what will provoke or amplify the effect. Scenes with bright sources of light (incommensurate with the gross ambience of the scene) and/or high contrast edges will almost undoubtedly result in SA, but other times you may be surprised to see it… or be surprised to not see it.

Contrary to what you might think, it is less of a problem during the daytime than it is at night. This is because night scenes typically display abrupt transitions in contrast, whereas daylight scenes are generally populated by neighboring areas of similar luminance values and the transitions between light and dark are usually smoother. This is why the above crops of the sign and blue shack are very sharp with little spherical aberration.

For example, if you’re out shooting at night, point light sources (e.g. a street lamp) within the frame will bloom heavily. Other light sources will display blooming and diffuse glow inversely proportional to the brightness of the source to the neighboring dark areas.

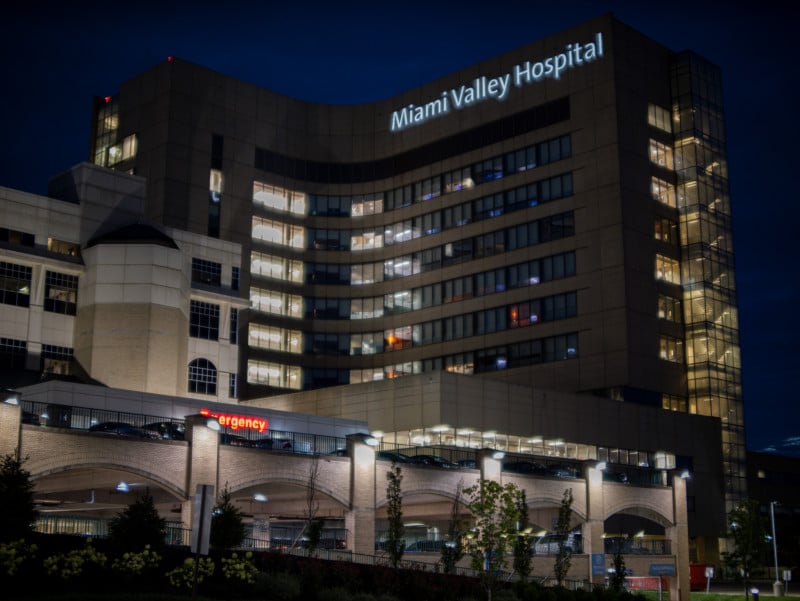

The below photo demonstrates what you can expect from shooting anything at night with point sources or high-contrast edges in the frame — in this case, the “Miami Valley Hospital” and “Emergency” signs have a pronounced glow, as do all the lighted windows. Likewise, all the point light sources like the garage lamps are bloomed.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Specular highlights, such as reflections off cars or metallic objects, will also bloom.

The major issue with the SA, aside from the “glow” which can be quite intense in some cases, is how it can overwhelm the image and rob it of microcontrast and resolution, as in the above photo of the parking meter. Photos may appear somewhat soft as if a thin veil has been placed over the lens. It’s not unlike the results from a shooting through a Pro-Mist (or other types of diffusion) filter, blooming included.

In actuality, the lens is not soft nor lacking in microcontrast — as we’ve seen, it is very, very good. Soft optics result in a global effect over the entire image, while spherical aberration is described locally.

As an example, areas of low contrast can still be quite sharp. This is a crop of the brick of the parking garage, which displays excellent resolution at f/0.95, despite being well into the outer periphery of the frame.

While all of this doesn’t sound great from the way I’ve written this (and it isn’t great in many cases), it’s important to note a few things: 1) this is not unexpected nor is it unique to this lens, and 2) given a realistic application of this lens, for most people, this may not be a huge problem. I test these lenses to purposefully provoke flaws. With that said, the unreliable nature of when you’ll get some intense SA does make it a bit more difficult to use.

It’s worth noting, particularly for those who might want to use the lens for astrophotography, that there is considerable coma wide-open, which you can see in some of the above photos. The spherical aberration alone would make it a non-starter for astro use, but I figured I’d point it out.

Bokeh

![]()

Bokeh is very smooth with a pleasant transition to out-of-focus areas and almost no spherochromatism. Even busy backgrounds melt away into an attractive blur. Bokeh balls do display very minor texturing in some situations, mainly wide-open, indicative of the presence of a molded aspherical element. But there are no ugly “onion ring” aberrations or anything of the sort.

There is significant optical vignetting — the blocking of peripheral light rays by the lens barrel and the increased distance of off-axis incident light. Since the effective shape of the entrance pupil progressively narrows as you move away from the optical axis, and bokeh balls take on the shape of the aperture, the result is an almond-shaped bokeh commonly known as “cat’s eye” bokeh. This becomes more severe as you move away from the center of the image due to the truncation of those off-axis rays. Once again, this is to be expected — even the $8,000 Nikon Noct-Nikkor 58/0.95 and $13,000 Leica 50/0.95 Noctilux suffer from it.

However, this lens exhibits more optical vignetting than I anticipated; anywhere outside of dead center will yield cat’s eye bokeh. This is due to the optical design of the lens and, I suspect, the placement of the diaphragm. Quite unusually, you can’t even see the aperture blades until about f/3.5 when viewed through the rear element.

Stopping down will result in some polygonal bokeh balls, so obviously, the nine aperture blades are not completely round. While the bokeh wide-open varies significantly across the frame, it cleans up quickly, and once you hit f/2.0 or so, everything is very uniform. I don’t mind polygonal bokeh balls personally, and the lack of any sort of onion ringing or other issues makes for, in my eyes, extremely pleasing bokeh. Aside from the cat’s eye, there is only some extremely minor texturing due to the molded aspherical element, and some very light fringing, neither of which is anything to complain about.

There are a few (very few) occasions when the bokeh can take on a busy, almost “soap bubble” look. I only noticed this twice, both times in photos shot at a medium distance (10-20 feet) from the subject with a lot of leaves in the background. Below is one example.

![]()

I don’t consider this to be a significant issue because most of the time, the bokeh is extremely pleasant with smooth bokeh balls and very little fringing.

As mentioned previously, the presence of SA does make focusing more difficult. The plane-of-focus transitions simply aren’t as enunciated as you would see with a highly corrected fast lens — a sharp plane of focus is what often results in the “3D look” descriptor.

![]()

So, instead, with this lens, you get a very smooth transition from the focus plane, which can make for some lovely portraits. After all, many of the most revered portrait lenses lack aspherical elements, and some of them, like the Nikkor AF-D 135/2 and AF-D 105/2 DC, even feature spherical aberration control.

I found the best way to nail perfect focus wide-open was simply to take a series of bursts and slowly rack the focus, ever so slightly. This is only an issue at closer distances — medium to far distances will have enough DOF that peaking and/or magnification will be sufficient.

Distortion, Vignetting, Flare, and Field Curvature

Vignetting: The least worrisome of optical maladies for me, but it is certainly present wide-open, though not extreme. There’s no Adobe profile at the time of writing, so you’ll have to dial in your own corrections if you need them. For a lens that’s most likely to be used for portraits and in low-light, it’s hardly anything to be concerned with.

Flare: One of this lens’s weakest points — it is extremely easy to encounter flare, even excessively so, when you wouldn’t even expect any at all. Most of the time, it’s light sources outside the frame that are an issue. It can be mitigated with the hood somewhat, but even that won’t save you. Normally I’d leave a lens hood behind if I was going out to shoot at night, but not here.

![]()

The flare takes the form of both veiling and ghosting, often both at the same time. Even with the hood, the only solution is to reframe or move, provided you notice it while you’re shooting.

Distortion: Very minor barrel distortion that is barely noticeable unless you have straight lines in your image. There is no Adobe profile for it yet but it’s easy to dial in a minor correction if you even notice it or care.

Field Curvature: There is no apparent field curvature.

Video Use

We don’t focus on video here at Petapixel, but given the design of the lens, it’s something that should at least be touched on.

The Laowa Argus 25mm APO features extremely well-controlled focus breathing; unless you’re racking from near the (very close) minimum focus distance to a much further distance, you likely won’t notice it. I’ve used plenty of high-end cinema lenses with more pronounced breathing.

The internal focus design of the lens is great for video as well; you don’t have to be concerned when using a matte box and if using a gimbal, there are no issues with a shift in balance.

![]()

One of the most overlooked aspects of fast lenses — and this applies to photography use as well — is the T-stop of the lens. In short, while the F-stop is the ratio of the entrance pupil to the focal length, the T-stop (transmission stop) is a true measurement of how much light passes through the lens. Since no lens transmits 100% of the light that enters it, the T-stop is always lower than the F-stop. While depth-of-field is affected only by the effective F-stop, the T-stop will determine your exposure.

It is extremely common for very fast lenses to have proportionally weaker T-stop measurements than their slower counterparts. For example, the Canon RF 50/1.2L has a T-stop of T/1.5, while the Canon EF 50/1.4 USM is T/1.6. This means the 50/1.2 only gives you a 1/6 stop faster shutter speed or lower ISO over the 50/1.4 — a big difference from the expected half stop.

While I don’t have the equipment to accurately measure T-stop myself, when compared to my SLR Magic 25mm T/1.5 Microprime, I see about a 2/3 to 3/4 stop difference. Bearing in mind that shutter speed and ISO work in 1/3 stop increments with a 1/8 stop margin of error, I’d estimate the Laowa to be around T/1.1 to T/1.3. Not bad at all.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Excellent Lens with a Caveat

I came away with somewhat mixed feelings after using the 25mm f/0.95. The lens vastly exceeded my expectations in terms of across-the-frame sharpness and chromatic aberration — it really is extremely impressive how well the lens resolves even in the periphery of the frame at f/0.95, provided spherical aberration doesn’t overwhelm the fine detail structure.

But if your work requires technical perfection, then you want to look elsewhere. While most of the lens’s issues clear up quickly as you stop down, there’s no point in buying a manual focus f/0.95 lens to use it at f/1.4 or lower. At that point, you might as well get something like the Panasonic Leica 25/1.4 Summilux II and enjoy the autofocus and smaller size.

So, if you can deal with situations where the SA will be present or potentially overwhelming, it is a great option. It also may be a great choice for video users for whom the spherical aberration isn’t an issue — it can make for a kind of “halation effect,” with bloomed light sources and highlights. Likewise, the apparent softness caused by the SA can be desirable to take the edge off today’s high-resolution hybrid and cinema cameras — again, much like the use of diffusion filters in video work.

Given the physical design of the lens, it seems that Venus Optics has built this with video users in mind.

Are There Alternatives?

The closest director competitor (in terms of specs, image quality, and build) is the Voigtlander Nokton 25/0.95 Type II, which is also a manual focus lens. The Voigtlander definitely wins out on build quality with a very robust all-metal build, beautifully scalloped focus ring, and an aperture ring that won’t induce a stroke from frustration, which can be optionally declicked. The Laowa Argus 25mm, however, bests it on image quality and, at half the price, represents a better value.

On the budget end, there is the Mitakon Zhongyi Speedmaster 25/0.95 and the 7artisans Photoelectric 25/0.95. With the Mitakon also clocking in at $399 and the 7artisans only $30 cheaper, the Laowa is the clear choice between these three.

![]()

If you don’t absolutely need f/0.95, the Olympus M.Zuiko 25/1.2 Pro is a fantastic alternative that’s superior to the Laowa’s image quality by a considerable margin, all while having the valuable benefit of autofocus but only being 2/3 of a stop slower. For video users, it features a manual focus clutch which gives you hard stops and linear focus for easy, repeatable focus pulling (throw is much less than the Laowa, though). It is, however, quite expensive comparatively at $1,399.99. But that’s the price you pay for world-class optics.

Finally, if you’re strictly a video user, you might be better served by the Mitakon Zhongyi Speedmaster 25mm T/1.0, SLR Magic 25mm T/0.95 Hyperprime, or 7Artisans Photoelectric 25mm T/1.05 Vision, as these are designed with 0.8 MOD focus gears, longer focus and T-stop ring throws, and are made to work easily with standard cinema accessories such as matte boxes. The SLR Magic Hyperprime is my pick of those, as I’m a huge fan of the rendering of SLR Magic lenses.

Should You Buy It?

Maybe. Overall though, Laowa Argus 25mm f/0.95 APO represents a very good price/performance ratio. When the image quality shines, I’ve never seen anything like it in a lens of this spec and price: extremely well-controlled chromatic aberration, excellent sharpness wide-open even in the edges and corners, and very good quality of build (minus that awful aperture ring design). Spherical aberration is almost always present to some degree or another at f/0.95, but as for how much this affects your work, only you can know that.