The Clever Cameras Used by the East German Stasi to Spy on Citizens

East Germany, or the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was one of the most tightly-controlled police states in recent memory from 1949 to 1990 that would spy on its own citizens throughout using all sorts of fascinating imaging equipment.

The Ministry for State Security, better known as the Stasi by its German acronym, was a fierce and shadowy secret police intent on keeping the Socialist Unity Party (SED) in power as a one-party communist state during the Cold War.

In January 1990, only two months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, protesters stormed Stasi headquarters in East Berlin in an attempt to stop its agents from destroying documents and force both East and West Germany to make them fully accessible to citizens upon reunification.

Ever since, the building has been a museum chronicling and documenting just how the GDR became such a police state and how the Stasi enforced the party line. To this day, citizens can make appointments to come in and see files kept on them, learning everything about why they were under suspicion — and who informed on them.

![]()

The stats are staggering unto themselves. At its peak, the Stasi employed 91,000 people, meaning one-in-30 GDR citizens were agents, while over five million (out of a population high of 16 million) were under suspicion or surveillance. Another 500,000 informants, either regulars or occasional, supplied information about anyone and everyone at one point or another. Neighbors, colleagues, classmates, and even friends and family spied on each other, though most would have no idea until the Stasi archive revealed just how pervasive its reach truly was.

Documenting the Lives of Others

The Stasi took 1.75 million photos and 2,800 reels of film to go with the mountains of files and audio recordings it amassed over 40 years. It used images to not only document what people were doing, but also develop public misinformation campaigns against “subversive elements” in the country targeting anyone perceived to have some sway over others in the population. In particular cases, agents wouldn’t even hide what they were doing in an attempt to intimidate the “target subject”, though these were rarer by comparison.

![]()

To pull it off, it took inventive steps for the time. Hidden cameras inside clothing or various everyday objects allowed agents or spies to capture movements and goings-on without being discovered. All sorts of everyday objects could fit the bill, like a West German watering can that was appreciated for its sturdiness, even down to basic things like trash cans and fake tree trunks. The museum mentions many of the items used in this way, but not all are on display, unfortunately.

Several are, however, like the French Beaulieu R16 movie camera, which was rejigged to use a pinhole lens and mirror to surveil a room, where they would’ve drilled into the wall to cut a hole just one millimeter wide on the other side to see everything by adjusting the mirror based on which part of the room to focus on.

There was the F-21, a Soviet miniature camera manufactured for the KGB starting in the 1950s. It was a favorite within the Stasi because it was small, light, and easier to conceal, like in the example here where it’s hidden behind a button, among other disguises, like a tube, belt, pocket, wallet, handbag, or various other items.

Even smaller was the Totscka, another Soviet miniature camera produced in the 1960s for the KGB, and essentially a design copy of the West German Minox Camera, a brand which originated in pre-World War II Latvia and continued in post-war West Germany. It wasn’t long before it became everyone’s favorite spy camera, prompting the Soviets to counter with one of their own and bring it to the Stasi.

Owing to Germany’s own storied legacy and pedigree in optics and photography, there were East German cameras as well. The Ihagee Exakta 500 from Dresden starting in 1966 was another common tool of the trade, though that brand’s legacy extends back to 1912, and produced arguably the first 35mm SLR in 1936 with the Kine Exakta (the Russians would argue the GOMZ Sport was the first).

VEB Pentacon, also based in Dresden, absorbed the Exakta line thereafter, helping further develop the Praktica line, including the MTL 50 35mm SLR that came out in a few different variants between 1985-89. Praktica first started with the M42 in 1949, but really took off with other models and variants from the 1970s onward, and still exists today under British ownership.

![]()

![]()

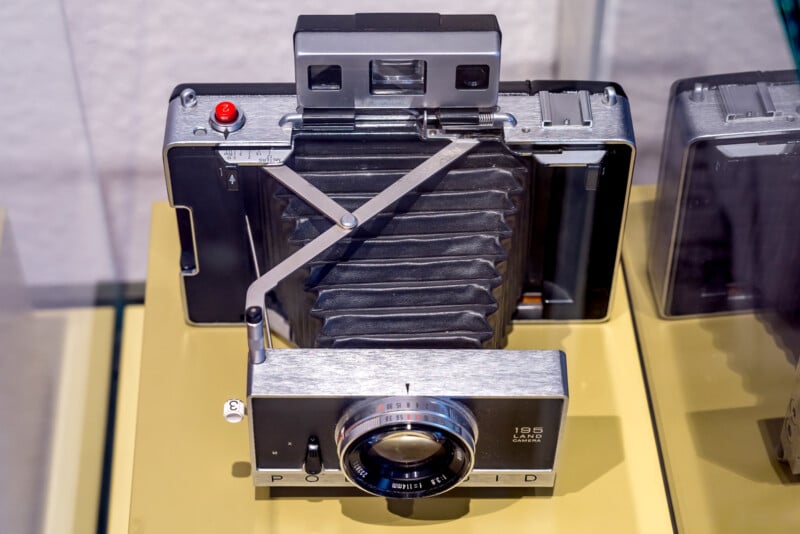

The SLRs were key for agents because there were plenty of interchangeable lenses capable of following a subject from further away without sacrificing quality. Their ubiquity among the population also made it easier for agents to blend in as tourists or working photographers, since there was nothing unusual about how the cameras looked or what they did. Stasi agents also used that kind of approach when on assignment abroad, especially in Western Europe. Some were adept at using Western-made cameras as well, which is why a Polaroid Land 195 is also in the museum.

The Stasi tried experimenting with different methods to automate certain features or controls, be it autofocus, automatic aperture, custom focal planes, shutter releases, and noise reduction. There was also a Pentacon GSK camera equipped with an attachment to carry extra film cartridges, enabling it to capture over 400 exposures taken at automatic intervals — usually positioned in public spaces like post offices. Engineers often worked with domestic camera brands to figure out ways to miniaturize, or in some cases, add to cameras to perform certain tasks that might’ve been trickier to manage.

Surveillance also meant being on the move and trying to stay inconspicuous day or night, prompting the Stasi to develop a flash within a passenger car door. Installed in the Trabant, East Germany’s own domestic car, they put in an infrared flash system made up of 13 rays that could produce the light of a flash when released together. A Carl Zeiss Jena rangefinder lens with laser autofocus attached to a GSK SLR camera would sync with the system to produce enough light to capture a good image using Kodak infrared film brought in from the West.

In order to even see through the door, the outer panel was made from Plexiglass and painted with a thin coat to exactly match the color of the car, which was usually white or a light color.

All told, the system had a range of 20 meters and the flash invisible to the human eye. It was terribly expensive to build, so only 25 were ever made and used in the field, but it did enable agents to take photos in almost complete darkness.

A Legacy in Mass Surveillance

It’s astonishing protesters restrained themselves from looting and trashing the Stasi headquarters back then. Because of this, there are a great many cameras and artifacts on display today. They even took care to leave the offices as they were. Erich Mielke was the notorious head of the Stasi from 1957-89, rapidly tightening its shadowy hold over the population. His office is pristine, with the same original telephones, along with one of the world’s first fax machines and even a secret recording device to cover meetings in his office. All look untouched, like they’re stuck in time.

Meeting rooms where East German and other officials from the Eastern Bloc would’ve met also have the same original furniture inside, including TVs and other objects that feel like stepping back into a very different time and place.

It’s fitting that the Stasi’s most pervasive period of covert surveillance was in the 1980s when technology made it easier, yet also while the entire Eastern Bloc was unknowingly heading toward revolution. It was in this period that the GDR saw tremendous societal pressures from youth in the form of social justice and environmental activists, as well as sub-cultures mirrored in the West, like poetry, music, skateboarding and even a rising far-right skinhead movement — all of which the Stasi had to contend with. A country and ruling party defined by conformity and loyalty to the state was slowly cracking until the Berlin Wall itself cracked and fell into irrelevance on November 9, 1989.

The museum covers this in great detail outside of the main entrance with a bevy of original photos covering all the various threads telling the story of the GDR/East Germany all the way up to German reunification in October 1990. But it also doesn’t imply bias, noting that not everyone in the population was against the SED regime, whilst others lamented the Wall’s fall and what it meant for their past, present, and future.

The outstanding 2006 German film, The Lives of Others, dives into the moral bankruptcy of such a surveillance state, telling a great story that humanizes those who surveil and those being surveilled. Its easy to wonder what the Stasi might’ve done with the Internet and modern digital imaging and data harvesting had it existed today.

Image credits: Ted Kritsonis for PetaPixel