Cameras That Changed Photography Forever

![]()

I write about a lot of things here at PetaPixel — reviews, guides, technical articles, opinion pieces — but one of my favorite topics to write about is the history of photography. As an avid user and collector of vintage cameras and lenses, I have passionately absorbed as much knowledge about their history as possible over many years. Like studying world history, there is much value in understanding where we came from and what got to us where we are now.

And so I have compiled a list of some of the most important cameras ever made that forever altered the photographic landscape. I know the comments will be full of folks asking why so-and-so wasn’t included or saying they can’t believe I didn’t mention a camera they feel I should have. So, I want to be clear: before cutting it down, my original list contained 69 cameras. Given that this article is over 6,000 words and only has 18 cameras listed, you can do the math and figure out why some had to be omitted.

That said, I present some of the most influential, preeminent, history-altering cameras ever made.

At a Glance

Daguerreotype (1839)

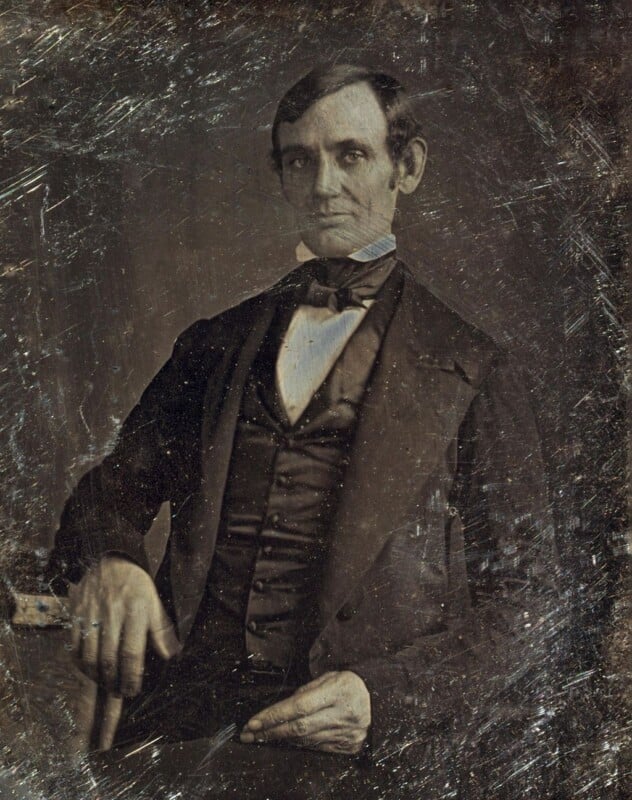

For the purposes of this article, we are going to ignore the camera obscura, as it was not a publicly available photographic camera. Toward the end of his life, Nicéphore Niépce — who used a camera obscura to produce the oldest surviving photograph in 1822 — worked closely with a fellow named Louis Daguerre. After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre inherited his notes and began experimenting with photographing images directly onto a silver-surfaced plate.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle at the time was exposure — Niépce’s “View from the Window at Le Gras” required an exposure to the tune of several days. But, in the mid-1830s, Daguerre made a breakthrough. He found that by fuming a polished sheet of silver iodide-coated copper with heated mercury, he could reduce the necessary exposure time to only several minutes.

On August 19, 1839, Daguerre and Niépce’s son Isidore presented to the world the first practical photographic process known as the daguerreotype. Unlike Niépce’s approach, which produced a “negative,” the daguerreotype formed a positive image. It was so popular that the French government purchased the rights to the design in exchange for lifetime pensions for Daguerre and Isidore, who were then allowed to release the technology as a gift to the world. Needless to say, the process was a massive success, even being used to take the first verified portrait of a United States President.

The daguerreotype would remain the most common commercial process for the next two to three decades until the collodion process replaced it.

The Kodak (1888)

In 1881, George Eastman, a bank clerk, and Henry Strong launched the Eastman Dry Plate Company in Rochester, New York. Eastman began experimenting with roll film in the mid-1880s and received a patent in 1885. Then he turned his sights to producing a camera that could use roll film. Three years later, he released the camera, known simply as the Kodak. For the first time in history, ordinary people with no real technical skills or knowledge could capture photographs.

The Kodak was a straightforward box camera with a fixed-focus 57mm f/9 Rapid Rectilinear lens. It had no viewfinder; on the top were two V-shaped lines, allowing for a rough approximation of the frame. A winder key on the top was used to advance the film, and the rotating barrel shutter was set by pulling a string. After a simple press of a button on the side, the camera would cycle the shutter and take the photo. The shutter itself operated only at a single speed of about 1/25 of a second. The result was circular images 2 1/2 inches in diameter, recorded on a 2 3/4 inch wide roll of film.

After finishing the roll, the camera was shipped back to Kodak, along with $10, and the film was developed, transferred to a glass sheet for contact printing, and a print was made. It was then reloaded and sent back to the owner. For those who wanted to develop their own photos, Kodak sold new rolls of film for $2.

The Kodak cost $25 ($808 in 2023) and effectively became the world’s first point-and-shoot camera, immediately becoming a massive success and launching a new landscape of amateur photography. “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest” was Kodak’s slogan. The Kodak now exists in the pantheon of photography history as arguably the most important camera ever made.

Kodak Brownie (1900)

I have previously written about the Kodak Brownie and how it changed privacy rights forever, but this list would be woefully insufficient if it weren’t mentioned again.

After the success of the Kodak, Eastman Kodak turned its sights toward expanding the amateur photography market. While the Kodak was a smashing success, it wasn’t particularly cheap, and its rotating shutter was highly prone to developing issues.

In 1900, Kodak unveiled the Brownie, cleverly named after the “Brownie” characters in Palmer Cox’s popular children’s books, which made Kodak’s advertising campaign incredibly fruitful. It was a simple leatherette-covered cardboard box fitted with a basic convex-concave meniscus lens, capturing 2 1/4-inch square photos on No. 117 roll film. The camera cost a mere $1 (about $36 in 2023), representing an approximately 97% drop from the cost of the Kodak. The exceedingly affordable price tag — especially for a camera that could be reused — launched Eastman Kodak into the photographic stratosphere.

In the first year, Kodak sold a quarter of a million Brownies, and within just five years, that figure was up to over ten million — it was a success far beyond the company’s wildest dreams.

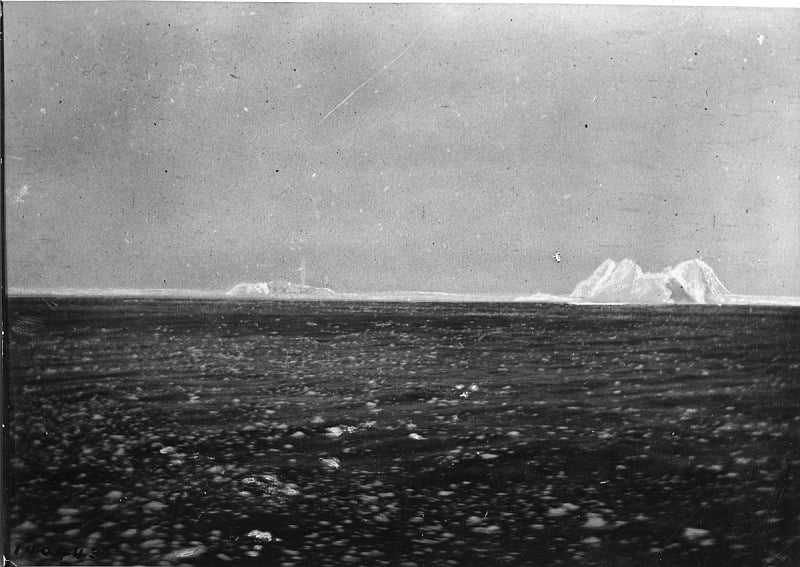

On April 11, 1912, seventeen-year-old Bernice Palmer was traveling aboard the RMS Carpathia from New York City, destined for Austria-Hungary. Four days after departing from the Big Apple, the ship diverted course, narrowly dodging icebergs for several hours, to rescue the 706 survivors of the Titanic. Bernice had been gifted a Kodak Brownie several months earlier, and she captured the first images of the survivors and the iceberg that sunk the infamous British passenger liner. In 1986, Bernice donated her Brownie and the photos to the Smithsonian.

Young Bernice Palmer and her Kodak Brownie epitomize the dawning of the incredible, world-altering phenomena that the cheap consumer camera established. No longer were cameras solely in the hands of professional photographers; no longer were they impractically large or prohibitively expensive. Without the Brownie, we may not have some of the most iconic and vital images taken over the past 123 years.

Graflex Speed Graphic (1912)

Before the advent of portable medium format and 35mm cameras, photojournalists and those who needed handholdable cameras primarily used press cameras. Press cameras were often large format collapsible bodies with track-mounted bellows. Lenses were easily interchangeable, focusing and framing were typically done via a large ground glass screen, flash could sync at any speed with common leaf shutter lenses, and they often included an optical viewfinder and occasionally a rangefinder. Press cameras were smaller, lighter, and much more portable than large format field or view cameras, though they had a reduced number and range of movements. Some contained both a focal plane shutter — allowing for very fast speeds and the use of barrel lenses — in addition to the leaf shutter. The most common format was 4×5 sheet film; the ability to use film packs and roll film (such as 120 or 220) was also possible.

In 1905, George Eastman acquired the Folmer and Schwing Manufacturing Company out of New York City. Two years later, it became the Folmer Graflex Division of Eastman Kodak. In 1912, the company released the first Graflex Speed Graphic. It had a focal plane shutter with a maximum speed of 1/1000th of a second — incredibly impressive for such a large format. It was available in sizes from 2.25×3.25 inches to 5×7, though 4×5 was by far the most popular. Using the camera was not a straightforward affair, especially when using the focal plane shutter — to set the desired shutter speed, the user had to set both a slit width and tension of the spring mechanism, with 24 various combinations.

Nevertheless, the camera became a huge success — many of the most iconic photos of all time were taken on Speed Graphics. They remained the go-to option for many photojournalists until the 1950s and 1960s when medium format TLRs and 35mm cameras superseded them.

The Speed Graphic continued to be produced — in numerous versions — until 1973.

Leica I (1925)

In 1913, German engineer Oskar Barnack of Leitz Wetzlar began experimenting with 35mm cinema film for use in a stills camera. Unlike motion picture cameras, which transported the film vertically, Barnack designed a camera to advance the film horizontally, expanding the frame size from 18x24mm to 24x36mm. There was one problem, though: existing 35mm lenses couldn’t project the necessary image circle to cover the larger negative. Barnack turned to Professor Max Berek to develop the first lens designed specifically for the new 24x36mm frame. The result was a 50mm f/3.5 lens with five elements in three groups based on the venerable Cooke triplet. Initially named the Leitz Anastigmat, the lens was later renamed the Elmax (E Leitz + Max Berek).

The prototype camera, known as the Ur-Leica, was downright petite, and it was enough to convince Ernst Leitz II to greenlight a pre-production series of cameras for photographers to test in 1923. Despite receiving mixed feedback, Leitz decided to push ahead with production in 1924. Thanks to improvements in optical technology, Berek was able to redesign the lens to be both higher quality and cheaper to produce, resulting in a 50mm f/3.5 four element/three group lens now named the Elmar.

Announced at the Leipzig Fair in 1925, the revolutionary camera, known as the Leica I (sometimes referred to as the Model A), permanently put the 35mm format on the map. The compact, ergonomic design was a massive hit. It featured a horizontally-traveling cloth shutter with speeds from 1/20 to 1/500, a film-advance knob and frame counter, a rewind knob, and a small viewfinder for framing. The collapsible 50/3.5 Elmar was non-interchangeable, and the lack of the rangefinder meant it had to be scale-focused. But those shortcomings were of little concern at the time. The Leica I was a watershed moment that would come to define the direction of photography well into the 21st century.

Kine Exakta I (1936)

In 1936, Ihagee Kamerawerk Steenbergen GmbH of Dresden announced the Kine Exakta. This release represented the world’s first 35mm SLR to see mass production. While the single-lens reflex design was not new, Ihagee put a lot of resources into creating a small 35mm SLR. One obstacle was that ground glass — which would be quite small for a 35mm camera — would make it impossible to focus accurately. So, a Plano-convex magnifying glass with one ground side was used to create a focusing screen in the finder. Additionally, much like many medium format TLRs, a magnifying glass could be popped out to achieve critical focus.

Ihagee also had to design fast lenses to amplify the amount of incoming light and enhance visibility in the finder. It turned to Carl Zeiss Jena, who produced a 50mm f/2.8 Tessar, followed by the Biotar 50mm f/2 and Schneider-Kreuznach 50mm f/2 Xenar.

The Kine Exakta was hardly the most elegant camera ever built, and its image in the viewfinder was laterally reversed. Still, it was the first camera that truly set the stage for the future dominance of SLR technology.

Hasselblad 1600F (1948)

Before 1948, Hasselblad’s only cameras, such as the HK7, were aerial cameras produced for the Swedish military during World War II. After the war, Victor Hasselblad turned his attention to the civilian photography market with the goal of creating the “ideal camera.”

The resulting camera, introduced in October 1948, was initially known simply as the “Hasselblad Camera,” but it would later be designated the Hasselblad 1600F after its 1/1600 sec maximum shutter speed (“F” was for “focal plane”). It was notable for being the world’s first mainstream medium-format SLR (the first in general was the Pilot 6) and for its design as a system camera — its modular design that enabled users to exchange viewfinders, film backs, and lenses was a novel approach at the time. A decade later, producers of 35mm cameras began to adopt the modular design approach.

The 1600F was the beginning of one of the most legendary and respected brands in the history of photography. Nine years after its release, Hasselblad debuted the 500C, the first in a line now known as the “V” system. The modular approach remained in the V system and endured for 75 years until Hasselblad discontinued the H system earlier this year. Even modern digital backs like the CFV II 50C can be used on the original 500C.

Hasselblad is also famously the first (and only) company to put a camera on the moon.

Leica M3 (1954)

By the 1950s, Leica had established itself as the premiere manufacturer of high-quality 35mm cameras and lenses. But all of its models since the Leica I were relatively incremental updates.

So, in 1954, Leica released one of the finest cameras ever made: the Leica M3. It used a new bayonet M mount instead of the thread mount in previous Leicas. This made it quicker and easier to unmount a lens and mount a new one, also providing a more secure attachment. Furthermore, Leica Thread Mount lenses could still be used on the M mount with an appropriate adapter.

The M3 featured a viewfinder and rangefinder combined into a single window. This was a first for Leica, though other cameras, such as the Contax II, had such a design for years. But the M3’s viewfinder was novel in one significant way — it was extremely bright, with a massive 0.91x magnification. It only contained framelines for 50, 90, and 135mm lenses. However, Leica offered an accessory shoe finder, and some lenses were paired with auxiliary lenses (often referred to as “goggles”) that sit in front of the viewfinder to widen its field of view.

Unlike the Barnack Leicas, film loading was significantly more manageable thanks to a hinged flap on the rear of the camera, allowing for easier film positioning when loaded through the bottom.

Production of the M3 continued for twelve years until 1966. A massive 220,000 units were sold over that time, and numerous online sources claim it is Leica’s most successful M series model — Leica themselves once told me the M6 was its biggest success, but either way, the M3 is undoubtedly one of Leica’s pinnacle achievements.

The M mount is still in use today, making it the oldest mount for which cameras are still produced.

Nikon F (1959)

I have already written at length about how the Nikon F revolutionized photography, but this is a camera worth a quick recap.

As we’ve seen with the Kine Exakta, the Nikon F was hardly the first SLR. It wasn’t even the first SLR with a pentaprism viewfinder — a lens projects an image that is both laterally and vertically reversed, and the reflex mirror projects it re-inverted but still laterally reversed. A pentaprism, however, uses two additional mirror surfaces angled at 90 degrees to laterally flip the image back to normal. Italy’s Rectaflex and Germany’s Zeiss Ikon Contax S, released in 1948 and 1949, respectively, contained the first eye-level pentaprism finders. But it was arguably the Nikon F — the first system camera with a roof pentaprism — that cemented the design as the standard until the emergence and market dominance of mirrorless technology about six decades later.

Nippon Kogaku (Nikon) saw an opportunity with the SLR, which had yet to take hold in any substantial way — the rangefinder still reigned supreme. So, under the leadership of Masahiko Fuketa, head engineer at Nippon Kogaku, and with the aesthetic prowess of graphic designer Yusaku Kamekura, the development of the Nikon F began in 1956. The goal was to take the clunky and complex quality of the existing SLRs and turn it into something elegant, polished, simple, and progressive.

Several years later, the team locked in the Nikon F’s final design, debuting a camera that boasted a lineup of true advancements: an instant return mirror (first debuted in the Pentax Asahiflex II), interchangeable viewfinders and focusing screens, titanium shutter focal plane shutter, removable back, mirror lockup, an auto-aperture stop-down mechanism for open-aperture focusing and depth of field preview, extraordinarily rugged build quality, and an impressive array of high-quality optics.

There was nothing else on the market that combined all these incredible features. For the first time, professional photographers had a 35mm system that could not only meet their existing needs but also open new avenues. Using any focal length — from wide-angle to macro to telephoto — was now feasible, as was the use of zoom lenses. Through-the-lens metering — which was first featured in a prototype Nikon rangefinder known as the SPX — when paired with the Photomic prism finder, was likewise a godsend for many photographers.

While the Nikon F didn’t invent many of its most substantial features, it is the camera that managed to fuse all those elements into a single camera body. It became one of the most popular professional cameras ever made and cemented Nikon as one of the world’s most esteemed — and popular — producers of photography gear.

Canon AE-1 (1976)

The first Canon SLR, the Canonflex, was introduced in 1959. Before that, Canon was primarily known for its excellent optics — particularly those in Leica Thread Mount — and its rangefinder cameras, such as the Canon IIB, Canon IVSB, Canon VT, and Canon L1 and L3. In 1964, Canon released the Canon FX and Canon FP, which introduced the Canon FL lens mount, moving away from the Canonflex’s R mount. Then, seven years later, in 1971, Canon debuted the Canon F-1 and Canon FTb, which now featured the FD mount. The FD mount was based on the earlier FL mount, and FD mount cameras can use FL lenses in stop-down metering mode.

The Canon FD mount was odd — it was a breech-lock mount, which, unlike a typical bayonet mount, would attach to the camera via a rotating ring on the base of the lens. This had the advantage of less potential wear to the lens’s contact surfaces since the lens itself does not rotate against the mount, such as in a bayonet design. The new FD mount also allowed for automatic aperture control along with full-aperture metering,

In 1976, Canon released what would become one of the most popular SLRs ever made — the Canon AE-1, which sold an unprecedented 5.7 million bodies. Its success opened up an entirely new market for consumer-focused SLRs, which exploded in popularity in the 1980s. It also holds the historical significance of being the first SLR with a microprocessor. The camera itself isn’t particularly special (aside from its microprocessor), and Canon made the odd choice of opting for shutter priority exposure mode over aperture priority (of course, full manual was available too). But it was a resounding sensation that was inarguably the genesis of Canon’s rise to photographic dominance, which persists to this day.

As an interesting piece of trivia, Apple sound designer Jim Reekes recorded the sound of his Canon AE-1 and used it for the screenshot sound on Macintosh computers and later the “shutter” sound on the iPhone’s camera.

Kodak DCS 100 (1992)

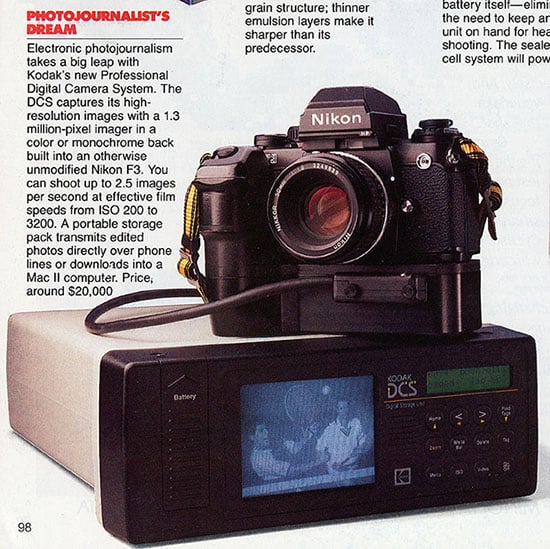

In 1991, the first digital SLR camera hit the commercial market in the form of the Kodak DCS 100. While we now associate the Kodak name with film, the company was one of the early pioneers of digital photography, particularly throughout the 1990s.

The DCS 100 body was formed from two primary components: a slightly modified Nikon F3HP body and a customized camera back fitted with a 1.3-megapixel Kodak CCD sensor. The F3HP body was chosen because it was the most popular professional camera at the time of development; the contacts for its motor drive also proved sufficient to synchronize electronic information between the body and back.

As the sensor measured 20.5 x 16.4mm, the camera featured a crop factor of about 1.65 diagonally in a 5:4 aspect ratio. Because of this, masks were installed in the viewfinder to indicate the actual capture area of the final image. Interestingly, the DCS 100 was available with either a color or monochrome sensor, and several were manufactured without IR filters. This was a trend that would continue with all future Kodak DCS models.

Unsurprising, the first commercial DSLR had several serious drawbacks. Aside from its astronomical $20,000 price tag ($45,000 in 2023), the DCS 100 required an external DSU (Digital Storage Unit) — larger than the camera itself — to be connected to the camera body via a SCSI cable and worn on a shoulder strap. It contained a 3.5” SCSI hard drive with a whopping 200 megabytes of storage, which was suitable for up to 156 uncompressed images or about 600 images using JPEG-compatible compression. There was even an optional keyboard that would allow the user to input captions and metadata.

For reasons I probably don’t need to explain, the DCS 100 was highly impractical and never broke into the mainstream. A total of 987 units were sold.

But that doesn’t stop it from making the list. Its successor, the DCS 200, debuted the following year with a significantly condensed storage and battery module (now using simple AA batteries) mounted onto the base of the modified Nikon F-801s (aka N8008s) body.

Two years later, Kodak followed that up with the DCS 400 series — now built around the Nikon F90 (aka N90) film body — which swapped the 3.5” hard drive with a PCMCIA card slot, and a new 6-megapixel APS-H sensor was offered in the DCS 460. From there, the rest is history.

Nikon D1 (1999)

The 1990s were marked by the near-monopoly of Kodak in the professional digital camera market. The Nikon D1, officially announced in June 1999, was Nikon’s answer to Kodak’s dominance. While Kodak had released many models in the years prior, they were all built around Nikon and Canon 35mm film bodies. The D1 was the first digital SLR produced entirely in-house.

But that wasn’t the only milestone the D1 holds claim to; it’s also the first practical DSLR, both in terms of usability and affordability. Its nearest competitor within the Kodak DCS series cost at least $12,000 ($22,000 in 2023). The D1 debuted at $5,500, less than half the price. It was an extremely capable camera that would ultimately end Kodak’s reign within the professional digital market.

Built off the general design and button layout of the Nikon F5, the D1 made for a near-effortless transition from film to digital. But perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the camera was its sensor. In the mid-90s, Nikon formed the ambitious goal of producing its own professional-grade digital camera for only a few thousand dollars. To begin with, no manufacturer would agree to develop the sensor, believing it was unrealistic for such a low price. Eventually, however, Nikon found a manufacturer but experienced trouble with the initial prototypes, which required several watts of power. Determined to create a camera that could be powered by a small (for the time) battery and shoot at high continuous frame rates, Nikon began to develop the circuitry itself. After two years of development, Nikon solved the problem by employing the same circuit technology and image processing used in industrial HD video cameras. Unusually, the sensor even used the NTSC color space standard instead of Adobe RGB or sRGB.

Measuring 23.7 x 15.6mm, it was a DX (APS-C) format CCD sensor with a final image output of 2.7 megapixels and a high base ISO of 200. The sensor performed shockingly well throughout its entire sensitivity range (ISO 1600 was the maximum). It was later revealed by Nikon that the sensor possessed 10.8 million photosites with what Nikon called a “quadra filter.” This allowed the sensor to bin (combine) four pixels into one, resulting in excellent high ISO sensitivity and dynamic range. The D1’s sensor was effectively the precursor to Sony’s modern Quad Bayer design. Nikon’s achievements with image circuitry and processing were made all the more impressive considering the 4x higher resolution and incredible five-frame-per-second shooting rate.

The release of the Nikon D1 formally inaugurated the ascendency of digital photography as a viable alternative to analog film and entrenched Nikon once again as an industry leader.

Canon EOS-1Ds (2002)

Contax, one of the unlikeliest candidates, was the first to produce a full-frame digital camera with its Contax N Digital and its Philips 6MP CCD sensor. Announced in late 2000, it was short-lived, as reviews were mixed, and sales were quite low. Contax withdrew it from the market less than a year after its release.

And so, it wasn’t until the release of the Canon EOS-1Ds in 2002 that full-frame became a viable reality on the consumer market. At that time, most DSLR sensors were APS-C, yet a vast majority of photographers were using full-frame lenses carried over from the film era. Among other issues, this made wide-angle photography quite tricky, given that very wide-angle lenses at the time were either non-existent, of poor quality, or extremely expensive.

The Canon 1Ds featured an 11.1MP — relatively high for the time — CMOS sensor, which made it rather unusual in a time of CCD dominance. Its electronically controlled shutter had a maximum speed of 1/8000th of a second with flash sync at 1/250th. The native ISO ranged from 100 up to a maximum of ISO 1250. A glass pentaprism viewfinder offered a rare 100% coverage, and autoexposure was accomplished via a 21-zone TTL meter that allowed for evaluative, partial, spot, and center-weighted modes. Its molded magnesium body with an integrated vertical grip that housed a large battery was superb, complete with full weather-sealing at every compartment, connector, and button.

Perhaps above any other camera, the 1Ds cemented Canon’s stellar reputation among professional photographers in the digital era.

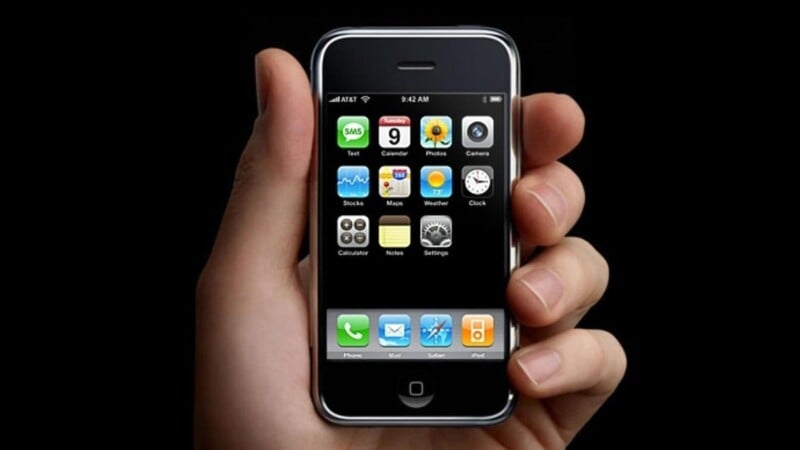

Apple iPhone (2007)

Primarily known in the mid-2000s as the company that made Macs and iPods, Apple had long toyed with the idea of a touchscreen device that would allow users to interact directly with their fingers. The development of the iPhone officially began in 2005, with its release hidden from the public until its announcement on January 9, 2007. It would be over a year and a half before the first Android smartphone, the HTC Dream, was released, with many dubbing it an “iPhone clone.”

The Apple iPhone was one of the most massive successes in modern technological history. Thousands of people reportedly waited outside Apple and AT&T stores days before the launch, and most stores sold out their stock within only a few hours. A mere 74 days after the release, Apple sold its one-millionth iPhone. It instantly became Apple’s most successful product and kickstarted a path that would lead Apple to become America’s most profitable company.

They say the best camera is the one you have with you, and that’s what the iPhone was. It didn’t have a great camera — a tiny 2MP sensor was hardly anything to write home about — and it wasn’t even the first smartphone with the ability to take photos. But it was the first to introduce mobile photography on such a massive scale. It would only be five years before the digital camera market peaked, with smartphones driving the enormous decline in camera sales.

For better or worse, the Apple iPhone changed the history of photography in ways that only a few other products can claim to have done.

Canon 5D Mark II (2008)

When discussing cameras that changed photography forever, it would be embarrassing to leave the Canon 5D Mark II off the list.

Photography cameras have become decidedly hybridized over the last few years, particularly since the transition to mirrorless across most of the industry. Today, we have numerous cameras in stills-oriented bodies capable of cinema-level video quality — some are even Netflix-approved, like the Panasonic Lumix S1H. Some of these cameras even contain filmmaking features like DCI video, anamorphic support, in-camera LUTs, waveforms, false color, open-gate recording, timecode support, and even external and internal RAW video recording.

It’s possible and probable that none of this would exist if not for 2008’s Canon 5D Mark II. While the Nikon D90 was the first stills camera to shoot HD video (720p), the 5D Mark II was the first to record 1080 HD video. With a full-frame 21.1MP sensor, the 16:9 sensor area used to record video was very similar in size to VistaVision 35mm film and larger than traditional Super 35.

The large sensor and video specifications opened the gates for amateur and low-budget filmmakers to shoot high-resolution video with shallow depth-of-field to achieve what many considered a “film look.” Prior to the 5D Mark II, low-budget filmmakers were primarily relegated to camcorders with 3CCD Type-1/3” or Type-1/2” sensors — the latter sitting between Super 8 and Super 16 film with a 5.41 crop factor. But with the 5D Mark II, larger format video could be shot in 1080p high definition with easily accessible Canon EF lenses.

By today’s standards, the 5D Mark II’s video quality was quite awful. To achieve full-frame 1080 HD video, the camera used line-skipping, recording only every third line, which created significant potential for moiré. The 8-bit 4:2:0 H.264/MPEG-4 compressed files, with a paltry 38 Mbps bitrate, left little room for extensive color grading or other image manipulation, and the sensor’s slow readout speed meant that the rolling shutter was pretty bad.

And yet, it marked a new era for amateur and independent videographers and filmmakers and set us on the path toward stills-video hybridization within the camera market. It was even used to shoot an entire episode of the popular television show House and Noah Baumbach’s black-and-white indie hit Frances Ha. Even parts of 2012’s The Avengers were shot with the camera.

Nikon D3/D700 (2007/2008)

The year is 2007. The first commercially affordable professional camera was launched eight years ago. In the time since, camera technology has seen many changes — some more experimental, like Fujifilm’s SuperCCD sensors, and some profoundly impactful, like the advent of CMOS sensors. Canon dominates the market as the only surviving company to produce full-frame DSLRs. Nikon, which has been Canon’s adversary for decades, is struggling to compete.

Enter the Nikon D3 in August of 2007. Successor to the Nikon D2Hs and D2Xs, the D3 was Nikon’s new flagship camera body. Featuring a full-frame sensor — a first for Nikon — the Nikon D3 only sported 12-megapixels of resolution. By contrast, Canon’s flagship DSLR, announced the same month, was the EOS-1Ds Mark III with 21.1MP of resolution. But it didn’t matter because the Nikon D3 blew the competition out of the water with its impeccable dynamic range and high-ISO image quality.

While the Canon 1Ds Mark III had a native ISO range of up to 1600 (3200 as an extended option), the Nikon D3’s native range bested that by two whole stops (ISO 6400) and three stops in extended mode (ISO 25,600). The D3 was capable of nine frames per second (11 in DX mode), nearly twice the speed of the Canon’s five frames per second. The D3 also boasted a new Multi-CAM3500FX 51-point autofocus sensor, along with a 1005-pixel AE sensor that was used both for exposure and autofocus tracking via color information.

Rounding out some of the D3’s headline features: a new EXPEED processor, a 14-bit ADC (analog-to-digital converter), extremely low 12ms power-up lag, dual CompactFlash slots, a 3.0” 922,000-pixel LCD monitor with live-view, extensive weather and moisture sealing, and a Kevlar/carbon fiber composite shutter rated for up to 300,000 actuations.

The following year, Nikon released the D3’s little brother — the Nikon D700. Often heralded as the best DSLR ever made by Nikon, the D700 was a watershed camera that brought high-quality imagery and professional quality to those whose pockets weren’t quite as deep. I started out with a Canon T2i and moved to a used Nikon D700 in 2013. I still have that camera to this day, and it has seen everything from weddings to wildlife to landscape to macro and more.

In 2008, three of DXOMark‘s top four highest-scoring cameras were now Nikons. The Nikon D3 and D700 tied for third and fourth place, only behind Nikon’s own 24.5MP D3X and Phase One’s medium format P65 Plus. In 2009, Nikon released the D3s, which improved the D3 and D700’s low-light performance even further. It wasn’t until 2011 that the D3 and D700’s “Sports” score was bested by the Canon EOS 1Dx — though the Nikon D3s remained on top until the Nikon Df’s release in 2013.

A legendary camera, the Nikon D3 and D700 have developed something of a cult following, perhaps more than any other digital camera. And I understand why — I still have mine for a reason.

Sony a7/a7R (2013)

Between 2006 and 2008, Sony was the fastest-growing camera company in the DSLR market, reaching an impressive 13% market share in 2008, making it the third-largest DSLR company in the world. In 2010, Sony transitioned away from DSLRs over to SLTs (“single-lens translucent”). These cameras utilized a pellicle mirror — a semi-transparent fixed mirror that bounces some of the incoming light to a phase detection sensor. In a time when mirrorless technology was in its infancy, having both phase detection autofocus and live-view was an appreciable advantage for many.

While there were many mirrorless cameras before the release of the Sony a7 and Sony a7R — including the full-frame Leica M9 — none had combined a full-frame sensor with live view or the large shooting envelope the new a7 line afforded. At the time of their release, the a7 cameras were the smallest full-frame cameras on the market by a substantial margin, outside of a few niche Leica rangefinders.

The a7 and a7R — both built around the Sony NEX’s E mount — were announced together in October of 2013. The former featured a 24MP Exmor sensor, a hybrid autofocus system with 117 PDAF points, a maximum shutter speed of 1/8000th sec, and a 2.4-million dot EVF. The latter offered the same 36MP sensor with no low-pass filter from the Nikon D800/D800E but with contrast detection autofocus only. The bodies weighed just over one pound, making them the lightest full-frame cameras ever produced. There were numerous other shortcomings — a lackluster body with (at best) mediocre ergonomics, only lossy 11+7 bit RAW, abysmal battery life, and a polycarbonate (plastic) mount prone to breaking with heavier lenses. FotodioX even released a replacement brass mount for users to install.

Sony fixed that issue in the a7 II and a7R II by implementing a stainless steel mount. The second-generation models also added 5-axis IBIS — a first for a full-frame camera. The a7R II, in particular, received significant upgrades with a new 42MP Exmor R BSI sensor, hybrid autofocus with 399 PDAF points, electronic shutter, superior metering sensitivity in low-light, 4K video output with pixel-binning (full-sensor readout in Super 35 mode), uncompressed RAW, and an ergonomically superior design.

The original a7 and a7R started the photo industry on a path that would eventually lead to the near-extinction of the DSLR market — Ricoh is the only remaining company that actively produces DSLRs. The short flange distance of the cameras allowed users to adapt virtually any vintage lens, as well as DSLR lenses like Canon EF, even supporting autofocus with adapters such as those from Metabones. The instant popularity of these cameras was almost certainly driven in large part by the easy adaptability of existing DSLR and vintage lenses.

The modern state of photography owes a lot to Sony.

Sony a9 (2017)

In 2017, Sony raised the game once again with the release of the Sony a9. Five years earlier, the company had developed the first stacked sensors — the Type-1/3.06 IMX135, Type-1/4 IMX134, and Type-1/4 ISX014, with 13.1, 8.1, and 8.1 megapixels, respectively. These sensors launched Sony’s new Exmor RS line of sensors.

In 2008, Sony developed the first BSI (backside illumination) sensor, which moved the metal wiring that sat between the microlens and color filter array and the photodiode substrate to the rear, allowing for enhanced light gathering and faster readout. But there was still room for improvement. Conventional CMOS sensors place the photodiodes and pixel transistors on the same supporting silicon substrate. Stacked sensor designs separate the photodiodes and transistors into two layers, enabling ultra-fast electronic shutter readout.

The Sony a9 was the first interchangeable lens camera to feature a stacked sensor. It had a readout speed of 1/160th and could do blackout-free silent shooting at 20 frames per second. This all but eliminated the need for a mechanical shutter in most settings, along with super-fast frame rates and significantly improved autofocus since the camera could perform an enormous number of autofocus calculations per second.

Today, stacked sensors have become the de facto standard in flagship cameras. At this point, Nikon, Canon, OM System, and Fujifilm have also adopted stacked sensors in at least one model. And their performance has only progressed since the a9. In fact, the Nikon Z9 — which has the fastest readout of any ILC at 1/270th — was able to do away with a mechanical shutter entirely. Only the Sigma fp and Sigma fp L had previously done that, though they came with severe limitations because of that choice. Last year, the $4,000 full-frame Nikon Z8 debuted without a mechanical shutter. I suspect someday, we will see this across the board. And it wouldn’t be happening if not for the Sony a9.

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.