How Bad is GDPR for Photographers?

![]()

The EU has a new data protection law, the so-called GDPR, the General Data Protection Regulation, or as we Germans like to call it: “Datenschutzgrundverordnung” (Gesundheit!). The rules took effect on May 25th and so far it’s pretty chaotic: in the EU we cannot reach some newspapers in the outside world because they cannot comply with the new rules.

Just how bad is it?

If you’re a professional, then you will need to fix your customer relationship management, your website, your data security, and much more. Just don’t email those stupid GDPR emails if you run a newsletter — chances are, you’ll just make things worse. If in doubt, ask a lawyer. And there will be doubts.

If you’re just a mom or pop shooting pictures of your family, you should be fine. The GDPR does not apply to data processing “in the course of a purely personal or household activity.” But beware: if you have a million Instagram followers, your kid’s birthday party is probably not a “household activity” anymore.

If you’re a photo enthusiast, then things get tricky.

See, the GDPR sees photography as something even the first Terminator could do: processing personal data. Yes, your dreamy picture of that girl in the sunflower field is the “collection and sharing of personal data” in the eyes of a data protection officer. Many things in a photo are personal data: her face, the location, the time and date, and everything that is tied to her identity.

The legal consequence: you need to provide some kind of justification to take that picture and to put it on your hard disk or — god forbid — to share it on Instagram. If you’re a pro, you have a model release. If you’re just a friend, it’s out of the scope of the GDPR (again, “personal or household activity”). But an enthusiast sits uncomfortably in the middle.

Are you ready to comply with your data duties? To wipe out personal data of someone who files a complaint, years after you took his or her photo? Are you ready to find each photo you ever made for your Flickr portfolio and delete it upon request?

Street photography especially becomes a legal nightmare. You cannot get consent before you take the shot because that would usually destroy the moment. According to the data protection law, you’re not allowed to only ask for it afterward. If you take a picture as an event photographer, you might argue that taking pictures of visitors at a conference is “necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests” (Art. 6 lit f GDPR). You don’t need consent then.

But can you do that if you shoot that amazing shot of an elegant business guy in a light cone on the street? Probably not. And you certainly cannot do it when a child is in your picture. That “legitimate interests”-argument does not apply “where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child”.

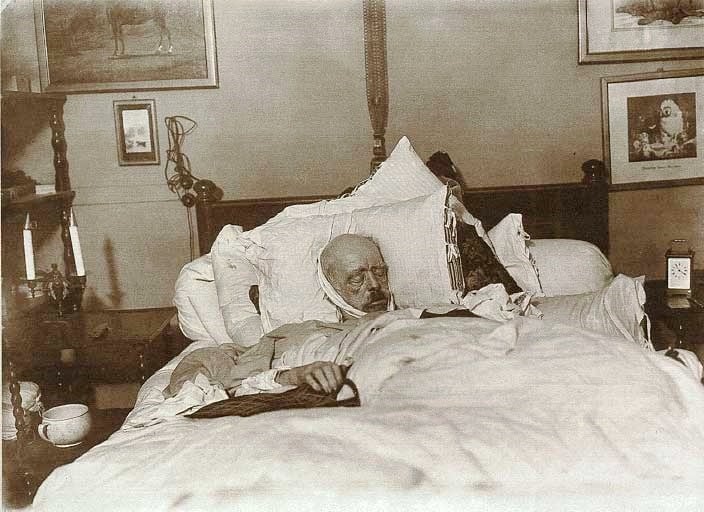

Of course, there were laws for photography before. Germany has had a law for photography dating back to 1907, when the Bundesrepublik was still a “Kaiserreich”: The Kunsturhebergesetz. You could be sentenced if you circulated pictures of people without their consent. It’s a reaction to the world’s first paparazzi: two photographers had taken a shot of the deceased Otto von Bismarck on his deathbed. Thank you, Willy Wilcke and Max Priester! People like you are the reason why we cannot have nice things anymore.

Over the years, our courts had found an acceptable balance between privacy rights and photography freedom. Very recently, the German Constitutional Court even ruled that street photography is protected by the constitution because it is “art”! Hear, hear!

That fair balance is at peril with the GDPR. The nature of an EU regulation is brutal and relentless: these laws come into force in every country and the courts have to ignore all national laws that contravene.

There is some hope though: some lawyers argue that the good old law from 1907 persists despite the GDPR. They cite Art. 85, a provision that deals with “Processing and freedom of expression and information”. It calls for Member States “to reconcile the right to the protection of personal data pursuant to this Regulation with the right to freedom of expression and information” — also for “artistic expression”, read: street photography.

Sweden seems to have such a law. Many other EU countries don’t, including Germany. Some argue that the old law from 1907 simply is such a reconciling law. But nobody knows for sure, and that’s the biggest problem: the legal uncertainty alone drives many photographers up the walls, especially in Germany.

The current situation is tragic: Germany should welcome street photography. While it may not be the birthplace of street photography, at least a German developed the tool for some of the most famous photography artists: Leica cameras! Also, in Heinrich Zille we had one of the first photographers who captured everyday scenes instead of posed pictures. As early as 1900 he showed Berlin of the Kaiserreich as it is. (Probably. There are people who doubt that it was really him who pressed the button.)

Don’t get me wrong. It is okay to learn from history. The EU has traditionally had a thing for data protection. We’ve had quite an impressive history with dictators and devilish intelligence agencies (e.g. Gestapo, Stasi), so we’re keen not to allow anyone to know too much about us. No wonder it was a German guy from the Green Party who pushed for the GDPR.

It’s also okay to look for a legal answer to mass surveillance and mighty Internet companies like Facebook and Google.

Still, it makes you wonder: are we doing the right thing when the outcome of a law is paralyzing legal uncertainty and, at least for photographers, not more liberty but less?

About the author: Hendrik Wieduwilt is an amateur photographer, journalist, and legal affairs correspondent based in Berlin, Germany. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of his work on his website, Instagram, and Twitter. This article was also published here.